Knowledge

Should You Use Sport-Specific Training?

Articles, Strength and performance, Training

Should You Use Sport-Specific Training?

You have all seen them on social media or even on TV sports shows: athletes doing resistance training exercises aimed at mimicking the structure of a sport movement. The logic is that by training in sport-specific coordination patterns, you more easily transfer the strength and power developed in the gym, to the field of play. You also have other types of “sport-specific” drills, which are more about balance and stability (like squatting on an unstable surface).

The idea is appealing. After all, when you see an athlete performing these drills with mastery, your brain automatically thinks, “wow, that’s going to help them in their sport,” or “he is super coordinated and stable, he will be a great player.” But is it a smart way to train an athlete?

You have two schools of thought. On the one hand, you have the generalist who sees strength training as a purely “general” (non-specific) training method. That allows you to get stronger and more powerful muscles. You tend to earn to apply that improvement in strength and power by practising your sport.

Proponents of that mentality will focus mostly on getting as strong as possible on the big basic lifts like the squat, bench press, deadlift, and rowing. Some will also use variations of the Olympic lifts. Here strength is seen as the main objective of resistance training.

Good examples of this would include Mark Rippetoe, Jim Wendler, Travis Mash.

The other group is the sport-specific group. Their focus in one using a lot of movements and exercises that have a coordination structure that is close to sporting actions. While they also use the basic lifts, they use a considerable proportion of exercises designed to emulate sporting action with their weight loaded exercises.

From my travels around the world, this is a prevalent mentality among European strength coaches. A good example is Frans Bosch.

The sports culture of a country has an impact on how their strength coaches think. Take football (American football). An off-season will last 6 to 9 months, depending on the level you play. That gives you a lot of time to focus on building general strength and then have plenty of time to do speed and agility work to transfer the gains you made to the sporting action. You could focus on building maximum strength for several months then have some more months to learn to be fast and explosive.

If you compare that to rugby in Europe, for example, their season often lasts 10-11 months! That leaves a very short off-season. They don’t see it as a good investment to spend a lot of time on building strength, and also they might not want to push strength development to its limit during the season where they do lots of practices and games. Sport-specific drills become an option that will have a greater bang for their buck as far as immediate results are concerned (but may limit future progression if strength is insufficient).

The Limitation Of Sport-Specific Work

I don’t like the term “sport-specific.” I prefer to talk in terms of “strength transfer exercises.”

I like to see exercises as development or transfer movements.

Development exercises will have the most significant effect on increasing strength (and muscle mass with the proper loading schemes). Transfer movements, by nature, do not build as much strength or power (in fact, they are pretty bad at this), but their coordination pattern allows you to learn to transfer the force you have to the more dynamic and complex sporting movements.

I like to describe transfer exercise as the bridge between strength training and sports practices.

I am not against transfer exercises. However, I am certainly against the improper use of said movements.

Take the bobsleigh guys I work. They squat close to 600lbs, front squat close to 500lbs. Deadlift over 600lbs. Gab power snatches 290lbs and Pat power cleans 355lbs.

In their case, the use of a moderate amount of transfer/sport-specific exercises will have a positive impact on performance. After all, their goal is to run faster to push the sled faster. Taking their squat from 600 to 650 lbs or their front squat from 480 to 540lbs will probably not make them any quicker.

Yes, strength plays a role in getting faster: it’s the foundation to power, and power is needed to sprint fast. Increasing strength will help you get faster… if your strength levels aren’t optimal.

But past a certain point just trying to get stronger will have a limited impact on speed. And it could be detrimental.

Strength is essential, especially for athletes who are not naturally explosive. However, increasing strength should mainly be mean to boost power, which helps produce more speed and agility.

It is possible to undermine speed by having tunnel vision about strength. Many strength coaches focus on strength as their primary objective as a way to prove their competence.

Let’s be clear: increases in strength will also increase the potential for power, and thus for speed. However, making this the sole focus of training can cause more harm than good.

- The three first qualities to be affected by neurological fatigue are speed, jumping, and grip strength. Training for strength, power, and speed all have a high neurological demand. Doing too much strength work can mask the ability to run fast by draining away the neurological resources, making them less readily available.

- At a certain point, increasing strength will have decreasing benefits on increasing power, if any at all. Increasing a squat from 225lbs to 440lbs will increase power (and speed) significantly. Bumping it from 440lbs to 550lbs will still help heavier athletes. But taking it to 600lbs+ will not improve speed and power much more.

- While the muscles adapt by becoming stronger, bones and ligaments stay the same. Tendons do not have the same rate of adaptation as muscles do. In the end, an increase in loading will carry more potential risks than rewards.

For example, Patrice and Gabriel don’t deadlift anymore. They can both lift 280-290kg/620-640lbs; the stress on the body is excessive for the potential benefits of taking that lift to even bigger weights. When they become capable of squatting more than 272.5kg/600lbs, they will stop pushing the back squat for maximum weights; instead, we will focus on the front squat. And if ever they get to a 272.5kg/600lbs front squat, they’ll switch to training mostly the split squat.

Hugo (short track cycling) increased his bench press from 100kg/222lbs to 140kg/308lbs. As a result, we stopped doing heavy bench pressing, as increasing it, even more, would have no added benefit for his sport. And it would increase the neurological demand and the risk of injury.

- Except in rare cases, no athlete needs to go past 272.5kg /600lbs in either the squat or the deadlift, or 3x bodyweight for a lighter athlete. At this point, it is best to use exercises that do not need such high loads (such as a front squat, incline bench press, Romanian deadlift, Olympic weightlifting) or to develop strength and emphasize the rate of force development (lifting explosively).

Don’t get me wrong: my philosophy is to get as strong, powerful, and fast as possible and then learn to apply those increased qualities to the practice of movements in sports. But you need to spend your training money where your return on investment will be more important.

What Do You Do When You Are Strong Enough?

I hate saying to someone that they are “strong enough”. My specialty is getting people stronger. And I’m a firm believer in developing an optimal level of strength in athletes. But even I must admit that there will come the point where the further athletic performance will not be improved by pushing strength even further.

What do you do to keep improving at that point?

You must switch your focus to more “rate of force development” exercises as well as on transfer movements (they are often the same).

Rate of force development movements focuses on speed and explosiveness. Jumps, throws, loaded jumps, power variations of the Olympic lifts, for example. Single leg and bilateral. You can also include loaded sprints, but with these, you must be careful not to have a negative transfer on sprinting mechanics (more on that in a moment).

As far as regular lifting is concerned, you should still lift heavy. You do not want to lose strength. Strength is essential for athletic performance. But you should not invest the same amount of work and resources on driving the big lifts even higher. At this point, it’s best to focus on moderate-to-heavy weights done with acceleration or emphasizing the eccentric or isometric action.

The Problem With Strength Coaches

But here’s the deal:

Very few athletes are strong enough!

Unless you are working with pros and Olympians, you will most likely train athletes that are FAR from being strong enough.

Understand one thing: “Transfer” exercises are there to help you learn to apply force and power in the fundamental movements like jumping, sprinting, throwing, or changing directions. They are the bridge between general strength lifts and sport skills.

But what if you don’t have much strength and power to transfer?

Here’s an example. Below is a progression of an exercise that I call the “Bosch clean” (from Frans Bosch):

The Bosch clean is essentially a single-leg power clean variation that includes a horizontal component as well as a vertical one. The main goal is to practice applying maximal force and power in the same vector as in a sprint.

I use it a lot with the bobsleigh guys I train (especially the level 1 which I very similar to the initial push of the sled) and track cyclists (mainly level 2 and 3). I also use it with football players.

But here’s the thing. If you go back to the two bobsleigh guys, Gab can power snatch 290lbs and power clean 350+. Pat hits similar numbers. They have plenty of strength and power to transfer.

I certainly would not use this exercise with a hockey player who can power clean 185-205lbs and squat 315. Focusing on getting stronger on the big basics will be a much better investment.

But exercises like these look cool. And in the competitive world of strength coaching, cool drills often take over effective ones because they help you seduce clients or look cutting-edge on social media.

Think “Transfer” Not “Sport-Specific”

Trying to copy a sporting action against a load, for example, throwing a heavy football or sprinting with a heavy sled, might do more harm than good.

If the coordination structure of an exercise is similar to a sporting action, there can be a positive transfer of strength and power to the sport. As I mentioned, see this as the bridge between strength training and the sport movement. But if the coordination structure is the same as the fundamental movement, you could have a decrease in performance through changes in movement mechanics or contraction velocity.

I’ll give you an example: a bobsleigh athlete was extremely fast. He ran a 6.36 / 60m (laser) and a 4.19 / 40 yards dash. He decided that he would try his hands at track and field to become the first white man to run the 100m under 10 seconds (that was close to 20 years ago, Christophe Lemaitre was the first one).

He hired a track coach whose theory was that if you did all your sprinting work with heavier insoles, it would make you sprint faster once you took them off.

The opposite happened. The athlete got significantly slower; I’m talking from 4.19/40 to 4.45+.

What happened is that the weighted insoles changed the sprinting mechanics: the heavier “feet” would have more momentum when pushing back, the back leg would overextend (without pushing more), then the athlete would have to use a slight outside loop to bring the leg back. The stride frequency got slower. Furthermore, the athlete learned to push a bit slower (more load leads to slower movement; the nervous system learned to apply force with a lower rate of force development).

To quote Charlie Francis, if a resisted sprinting drill leads to a drop in speed of 10% or more, it will lead to faulty mechanics and slower force application leading to a negative effect on performance.

Here’s the important thing: the more complex the motor skill is, the easier it is to mess the coordination pattern by overloading it. For example, it’s much easier to negatively impact the mechanics and velocity of a sprint or throw than that of a vertical jump (the later having a simple mechanic).

That’s why loaded jump squats are effective at improving power and jumping height, but loaded sprints or heavy throws are not always good. Note that loaded throws and sprints can be useful as long as the performance drop-off is less than 10%. But even then, the risk of a negative impact on performance is more significant than with simpler actions.

That’s why I like to use prowler sprints as a transfer movement toward sprinting: its coordination pattern is close enough to the sprint to have a positive transfer, but not similar enough to mess up mechanics.

The Transfer Drills That I Use

I use four main types of transfer exercises with athletes.

1) Accentuation strength drills

2) Loaded jumps

3) Olympic lift variations

4) Loaded sprints/Carries

You won’t see me use exercises that copy sports movements, though.

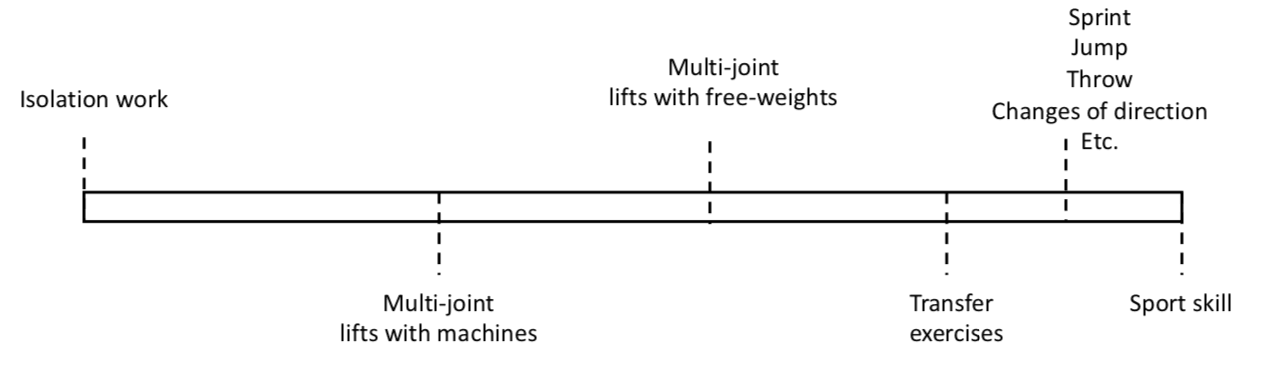

It’s a spectrum.

The transfer exercises do bridge multi-joint lifts and the fundamental motor skills involved in sports, like sprinting, jumping, throwing, etc. Mostly the transfer exercises are there to learn to apply force and power in the same coordination patterns as the fundamental movements used in sports.

Then the practice of those fundamental movements is used to transfer the physical capacities to the sport itself.

A loaded sport movement or something extremely sport-specific would fall between the fundamental movements and sport skills. And there is no need for that at all. Doing loaded sport movements would be a step backward on the transfer spectrum while trying to go forward. It would likely do more harm than good.

Accentuation Exercises

The principle of accentuation refers to doing strength work at the angle specific to a fundamental movement of a sports activity. For example, when you are sprinting, the smaller knee angle that you will have is 90-100 degrees. Being super strong from 90 to 180 (full extension) is thus something that will help you in your sport. And doing strength work in that range, provided that you have already built full-range strength, is a beneficial training approach to get there.

For example, with bobsleigh athletes, I will use the top half squats from pins during the transfer phase. To get them as strong as possible in the range of motion that is the most needed for their sport.

We can also switch to half squats (parallel) instead of full squats.

I do believe that full squats are the way to go most of the time with an athlete. But with someone with good full-range strength, the accentuation approach can be useful during the transfer phase.

You can also use the box squat for the same purpose. An international track cyclist that I train has noticed a direct correlation between his 90 degrees box squat and track performance.

Adding chains and bands while doing the full range of motion on the movement is another option. This still overloads the sport-specific amplitude while allowing you to keep training the full range of movement.

Loaded Jumps

Loaded jumps are my favorite transfer exercises. They have the most significant impact on jumping capacities and will also have a moderate effect on sprinting speed. The loaded split squat and Bulgarian split squat will have a more significant effect on running, mostly by improving stride frequency if you do them the right way.

Before we look at the exercises that I use, I want to mention two caveats. First, loaded jumps are very advanced drills. They should be used only by athletes who have a solid foundation of strength training but also great jumping and landing mechanics already.

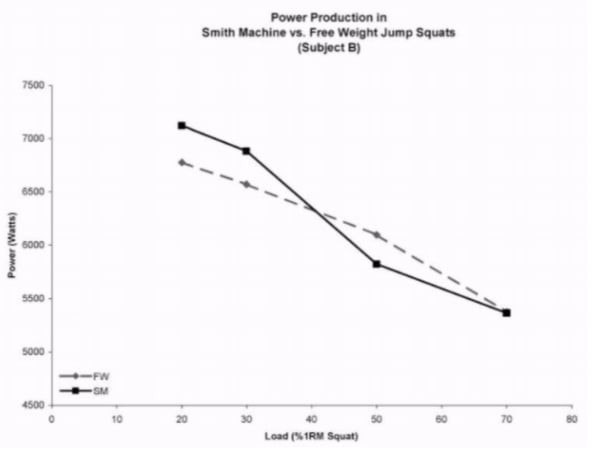

The selection of the load is also critical. I see people going way too heavy on these. The goal is not to progressively overload the jumps with more weight or to see with how much weight you can jump with. The goal is to jump with more power against a moderate load gradually.

The optimal load is the one with which you will have the highest power output.

For the loaded jump squat, we’re talking 20-30% of your maximum squat.

Using more weight than that will lead to less performance improvement and increases the risk of injuries.

Notice that we are not only focusing on producing as much power as possible on the way up but also on landing solidly, to develop the capacity to absorb force.

The second exercise that I use is the loaded Bulgarian jump squat. On this one, we use 10-20% of the athlete’s body weight. It is more complicated than it looks, at least if you want to get all of the benefits.

Let’s first look at the movement

The complexity of the exercises lies in the fact that you want to start by fully extending the drive leg on the jump, but then, as soon as you have reached full extension, you want to bring the knee toward your chest as explosively as possible. The latter is to improve stride frequency: being able to quickly bring the leg back after it’s done pushing on the floor. This is very transferable to sprinting.

If you don’t bring your knee up explosively, you are losing half of the benefits of the movement. But if you focus solely on bringing the knee up, you might cut your extension which will also not allow you to get all the benefits of the exercise.

The third loaded jump exercise that I use is the loaded jump lunge. It is similar in objective to the previous movement but has a higher level of complexity. That’s why I see it as a progression from the Bulgarian split squat jump. You would start with the BSSJ, and you would then move on to the loaded jump lunge.

To make the transition more productive, I like to use an unloaded split squat jump during the same phase as the Bulgarian split squat jump, to work on the coordination needed.

Then you are ready for the loaded jump lunge, on which you also use 10-20% of your body weight.

Notice that once again, the speed of the legs (when switching legs) is as important as the jump height. We have three key elements:

- Full-extension/maximum height

- Fast leg switch

- Solid landing

Olympic Lifts

The Olympic lift variations are often seen as general exercises (Multi-joint free weight exercises), much like a squat or deadlift. And if we are talking about the full Olympic lifts, or at least about the power variations from the floor (power clean from the floor and power snatch from the floor), it is correct.

I personally categorize the Olympic lift variations from the hang or blocks (power snatch/clean from the hang, power snatch/clean from the blocks) as transfer exercises.

An athlete who has proper technique on the full Olympic lifts would use variations from the floor in the developmental blocks and then switch to lifts from the hang during the transfer blocks.

The Single-Leg Lifts

One type of exercise that I like is the Bosch clean progression. I feel that they transfer well to learning to apply maximum force with the push/drive leg during sprints. I think it is especially effective at helping with the take-off.

I posted the videos of the three levels earlier in this article, but I’d still want to mention a few recommendations:

- Even level 1 Bosch cleans are still a single-leg movement. In the starting position around 80-90% of your weight is on the push/drive leg. There is only a small amount of weight on the swing leg, and it’s only for balance.

- The key is the push/drive leg (the one that is fully extended at the finish), not the swing leg (the one ending up on the box). You should push with the drive leg right until the end. Finish with that leg fully extended and on your toes.

- Even at the finish, you must have at least 50% of your weight on the back leg. If you find yourself losing balance or having the back leg bent, it’s because you have too much weight on the front leg.

Loaded Sprints/Carries

I talked about using loaded sprints earlier in the article, specifically how damaging it can be to sprinting mechanics and speed.

That’s why I prefer to use prowler sprints over the more traditional loaded sprinting methods (speed parachute, sled). It is close enough to a sprint to help transfer strength and power to the sprint action, but not so close that there will be a negative impact on the coordination pattern.

I also like loaded carries like farmer’s walk, Zercher carries, and the like as a bridge between traditional strength work on fundamental movements. Producing force while moving is closer in coordination pattern than only going up and down with a weight.

Loaded carries are not as close to the fundamental movements as the preceding three categories of transfer exercises are, but they still have value.

When And How To Do Transfer Exercises

It is important to reiterate that the purpose of transfer exercises is not to build strength but to learn to apply the strength you have in movements with a coordination pattern similar to fundamental movements like sprinting, jumping, throwing, or changing direction.

If you have a low level of strength to start with, you won’t have much to transfer, and the effect of these exercises on performance will be minimal.

Someone who doesn’t full squat at least two-times bodyweight shouldn’t focus on transfer exercises but rather on increasing overall strength.

The first introduction to transfer exercises would be the variations of the Olympic lifts (if you are competent at coaching them). Once an athlete power cleans at least 1.2 times bodyweight, he can think of introducing the other transfer exercises.

While you can keep a small amount of transfer work even during the developmental blocks of advanced athletes, most of it should be done in the 6-10 weeks before the season, or in-season. With athletes that have a very high level of strength, transfer, and rate of force development work can even become the focal point of those last two months of off-season training.

The way I program transfer work is as follow:

* In the early off-season of advanced athletes, I will use one transfer exercise per workout (usually 3 general movements), at the end of the session. I find that it helps facilitate the transfer in the future because you learn to practice applying force in a more “athletic” coordination pattern after you’ve just asked your muscles to produce force. At this point, we usually use the simpler transfer exercises.

Note that at this point, I often use the Olympic lift variations, since I consider them to be transfer exercises.

* In the later portion of the off-season, I often have 1-2 transfer workouts. In which we only do transfer exercises as well as the fundamental movements themselves (sprint, jumps, throws, agility work). These typically have 2-3 transfer exercises and 1-2 fundamental movements.

* During the season, since we can’t do as much work, I like to use 1-2 strength movements and one transfer exercise per session. In some sports where there is only one match per week or where there is not a competition every week, we could have 1-2 strength days and one transfer day per week — the transfer day being the workout closer to the match/competition.

-CT