Knowledge

Are You Neglecting 2/3 Of The Solution?

Articles, Crossfit, Training

Are You Neglecting 2/3 Of The Solution?

I am likely one of the main reasons why CrossFit athletes get injured. I also play a role in the higher non-contact injury rates in team sports as well as with athletes not being as fast or agile as they could be. I might even be one of the reasons why bodybuilders are not growing as fast as they could.

Who am I?

I’m the lack of emphasis on eccentric and isometric actions in training.

Three Functions

Your muscles can play several roles and contract in many different ways to produce various types of movement. But all of these actions can be divided into three broad functions:

– Overcome a resistance

– Hold a position against a resistance

– Absorb force

Overcoming a resistance refers to concentric muscle actions: producing force while the involved muscles are shortening. It is true that most athletic actions revolve around this function. When you are jumping, sprinting or changing directions you are pushing your body in a different direction, when you are hitting an opponent or pushing him away you are also working concentrically. In CrossFit, every time you lift a bar, jump onto a box, push a sled, swing a KB, pull your body up on a muscle-up or pull-up or push your body up on handstand push-ups, you are working hard concentrically. So not surprisingly, you need a high level of concentric strength to be able to perform. No doubt about that. But that is never really a problem since every weight training program is heavily slanted towards increasing concentric/lifting strength.

Absorbing force refers mostly to eccentric actions: producing force while the muscle is lengthening. Lowering a barbell back to the floor in a deadlift, going down in a squat, bringing the bar down to the chest in a bench press, are all examples. But it’s not limited to that: every time you land after a jump, strike the floor with your foot on each stride while running, have to break the lateral momentum before pushing the other way when changing directions, or when an opponent hits you on the football field, you are requiring a high level of eccentric strength. While some people do focus somewhat on increasing eccentric strength it is normally de-emphasized in most athletic/CrossFit programs.

Holding a position (position involving the whole body or parts of it) refers to isometric actions: producing force while there is no movement going on. Except for some very specific cases, pure isometric actions are rare in most sports, however, most movements, even the most explosive ones, have a brief but important isometric component. That phase or component occurs milliseconds before switching from absorption (eccentric) to overcoming/projection (concentric). When you are sprinting, you have to absorb your body weight every time you hit the ground, then you have to stop the downward/eccentric action before you can start the projection. The stronger you are isometric, the faster that transition can be. In that regard, isometric strength can be the difference between having OK speed and being FAST. And it can make a huge difference in making sharp cuts.

Concentric Dominance

Most training programs are heavily slanted toward maximizing concentric strength, especially in CrossFit and athletic training. The focus is on “lifting” more weight, going faster and jumping higher. This often leads to neglecting actions such as slow, controlled eccentrics, eccentric overloads and any form of isometric training. Let’s look at most movements involved in CrossFit and athletic training and how they are trained:

Kipping Pull-Ups – Explosive action with a high rate of force production during the concentric followed by almost a free-fall during the lowering portion of the movement. Extremely low emphasis on eccentric action.

Muscle-Ups – Same thing as with the kipping pull-ups. Emphasis is on proper positions during the ascent, but there is very little eccentric force production during the lowering portion.

Deadlifts – While you can do the eccentric/lowering portion of a deadlift under control, most CrossFit athletes let the bar drop quickly to use the rebound and make the reps easier/faster. In a competitive setting it’s fair game. You have to go fast or drop it down and reset on every rep (to save energy). So again, big emphasis on developing concentric strength, almost nothing to build eccentric strength.

Kettlebell Swings – By nature, the kettlebell swing is an explosive concentric action. Trying to stay relaxed during the eccentric/lowering phase is proper form.

Sled Pushing/Rowing Ergometer/Airdyne bike – There is zero eccentric emphasis on any form of sled pushing, or on the rowing ergometer and airdyne bike. These are all purely concentric.

Wall Ball – Sure, you’re squatting down so there’s some eccentric action. But the amount of force production is very low compared to the force produced during the concentric portion. In fact, during the eccentric/lowering phase of the wall ball, the athlete actually tries to go down as fast as possible, which requires “turning off” the muscles on the way down. So the quads, which would be loaded eccentrically during the descent, are actually turned down and the hamstrings/glutes pull you down faster (which is a concentric action not an eccentric one). The only true eccentric loading is at the point of reversal – when you switch back to going up – and this is mostly shock absorption done via the stretch reflex. Then when you project the ball, you produce more force because you have to produce upward acceleration. So again, you train the concentric action much more than the eccentric one.

Rope Climb – During rope climbs the effort is more intense when pulling yourself up the rope, which is almost all concentric and some isometric effort. On the way down, you’re actually using technique and friction to get down under control, not an intense muscular effort. So, the portion where you could actually develop eccentric strength by controlling the descent (with your muscle strength instead of friction) is pretty much rendered effortless.

Olympic lifts – Whether you are an athlete or a CrossFitter, when you do cleans and snatches (or their power variations) from the floor, normally you drop the bar on the floor after your rep(s) which minimizes the eccentric action of the movement, especially compared to the concentric action. CrossFitters will sometimes do “touch and go” snatches or cleans; meaning that they don’t drop the bar on the floor. While they do bring it down to the floor they are not really controlling the lowering portion, or at least not while producing a high level of tension and force; in fact, they will often speed up on the way down to catch a bigger bounce to help them lift more. If they do lifts from the hang there is normally a small eccentric action (lowering the bar down to the knees) but the amount of force produced is minimal compared to the concentric/lifting phase.

Jumps, plyometrics and agility drills – I will admit that during these actions the force absorption component is being trained. Landing after a jump or dropping off a box then jumping when doing depth jumps, or when switching directions during agility drills does require a good amount of absorption and reactive strength. The problem is that when you do these high demand exercises with an athlete who has not developed neither eccentric nor isometric strength through more direct and lower stress methods, they will simply not be able to absorb their weight properly. And just because an athlete is fast or agile, doesn’t mean that they are absorbing force properly. I think we’ve all seen this picture of Robert Griffin III, who was amazingly athletic, fast and powerful:

Is it that surprising that his career lasted only 2-3 years and that he had to undergo several knee surgeries?

In fact, most of the best “natural athletes” are good compensators rather than good movers. They are high-performance machines but can put themselves at risk more easily.

Jumps and plyometrics are not problematic if used properly and when the body is prepared for it. But if that is the only form of accentuated eccentric loading you have in your plan, you are bound to have problems.

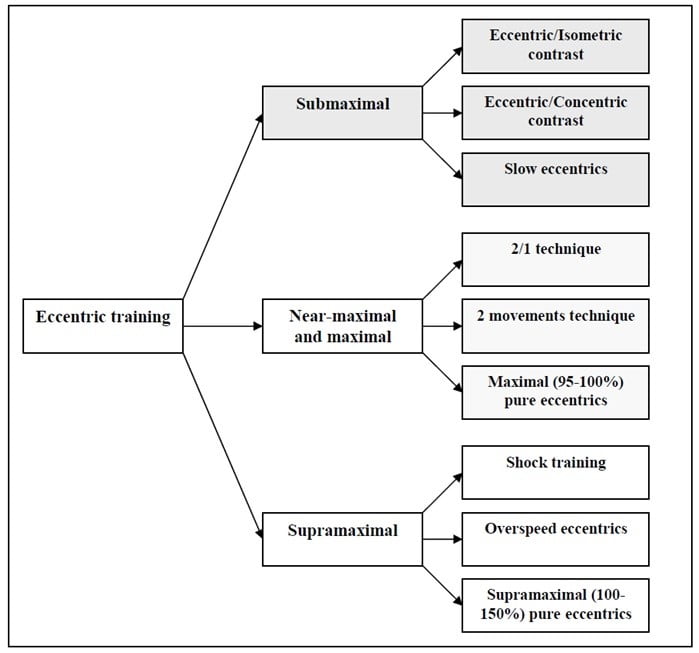

If you look at the following graphic from my book Theory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods, you can see that plyometric training (shock training) is among the most demanding form of eccentric training, if you have not built a foundation using the two other categories first, you will run into problems or at the very least, will have poor results.

Why Is Eccentric Strength So Important?

Eccentric and concentric actions use different motor strategies, so it’s possible to strengthen one without significantly strengthening the other.

Eccentric actions tend to strengthen the distal portions of a muscle more so than the middle portion of the muscle belly. (It’s not bro science, look it up.) They also tend to recruit fewer muscle fibres but a greater proportion of fast-twitch fibres.

During eccentric actions, intramuscular friction is your ally. During concentric actions, it’s your enemy. So, if you’re focusing on only one, it doesn’t mean that you’ll improve both to the same degree.

1. Eccentric work strengthens the tendons more than concentric and isometric actions. Stronger tendons mean a greater overall strength potential and a lower risk of injury.

2. Eccentric work increases your capacity to recruit fast-twitch muscle fibres. The better you become at recruiting these, the more easily you can gain strength and power.

3. Doing controlled submaximal eccentric work (slow eccentrics) improves motor learning and strengthens the body’s capacity to maintain optimal positions during your movements. This will make you more efficient, which means you’ll waste less energy in competition.

4. Supramaximal eccentric work on the big basic movements will strengthen the core/stabilizer muscles. They also desensitize the Golgi Tendon Organs which are basically protective mechanisms preventing you from producing too much force. The more desensitized the GTOs are, the more force you can produce even without adding muscle mass.

5. Handling supramaximal weights on partial or eccentric exercises will also give you more confidence when lifting heavy, but not maximal weights. These will feel lighter after doing supramaximal work and you’ll suffer less psychological inhibition.

Most people should emphasize eccentric actions first by including sets or exercises where the lowering portion is done slowly (5-6 seconds) while trying to produce maximum tension.

As an athlete becomes very efficient eccentrically he can begin to include heavier forms of eccentric training.

Why Isometric Strength Is Important?

While being strong isometrically can make you faster and more agile by allowing you to more rapidly switch from eccentric to concentric during explosive movements, I also love isometric training for other reasons:

1. To improve the mind-muscle connection. Yielding isometrics (holding a weight) for 20-30 seconds just prior to doing reps with that weight will allow you to better feel the targeted muscle, which will increase your capacity to make it grow. Here is an example:

2. To teach and automatize the perfect position in a movement. I like to use Holds lasting 30-45 seconds (no reps being performed) in a key position of a big compound movement really emphasizing creating maximum tension. This is a great way to learn and improve technique while developing the capacity to stay tight when doing the exercise.

As a coach, these long-duration isometrics also give you a large window of coaching opportunity to correct the athlete’s technique, posture and muscle activation.

3. During maximal isometrics (overcoming isometrics; pushing or pulling against an immovable object as hard as you can) you can recruit up to 10% more muscle fibres than in other types of muscle actions. They can thus be very effective in less experienced or less neurologically efficient athletes by programming their nervous system to be more effective at recruiting high threshold muscle fibres.

4. A good introduction to plyometrics is the use of depth landings: Standing on a box, drop off and land in the optimal jump position, trying to create maximal tension right upon landing. Try to “stick the landing” (not having a soft landing where you have to squat down to absorb the force). As an introduction method, the box should not be too high, the goal is simply to learn how to land solidly not to drop from a 3-story building! Remember, before you can train to jump you must train to land.

Conclusion

Regardless of whether your goal is to become a better athlete, reduce the risk of injuries, build more muscle or get stronger, you should not neglect eccentric and isometric training. While they do not need to be trained as much as regular lifting exercises, 20-40% of your training volume should include some form of isometric or eccentric emphasis if you want maximal development and performance, especially as a less experienced or younger athlete who is still building a foundation.

-CT