Knowledge

Training For Power

Articles, Strength and performance

Do you want to jump higher?

Run faster?

Hit harder?

Be quicker?

If you do, one thing you absolutely need to focus on is increasing your capacity to produce power. Power refers to being able to produce large amounts of force quickly.

Several tools are used in the gym to become more powerful. Ranging from heavy lifting all the way down to plyometrics and bounding drills. Which ones work best? How should you train to become more powerful?

In this article I want to address four of the most popular ways to use lifting exercise to increase your power production potential.

What Are The Best “Lifting” Exercises To Improve Power?

The main lifting approaches that are programmed with the purpose of increasing power output are:

1. Variations of the Olympic lifts: Coaches will use the clean or snatch movements, with the clean being more common. Typically, the “power” variations (caught at a knee angle of 90 degrees or higher) are preferred as they are less technical/easier to learn. Many coaches also prefer the variations “from the hang” (where the bar is lowered to around the knee level and then you explode up) because it is also easier to learn and more specific to sports.

2. “Olympic” high pulls: These are training exercises derived from the clean or snatch. In these movements you only perform the pulling phase of the lift, not the “catch”. They are thus even less technical than the other variations of the Olympic lifts. They can also be done from the hang position, blocks or the floor.

3. Loaded jump squats: In this movement you normally squat down to the power position (knee and hip angle of around 90 degrees) and jump as high as possible. There are also single leg variations like a jump split squat or jump Bulgarian split squat which are more complex.

4. “Speed” squats (or other traditional lifts): This is when you use a lift a moderate load (50-70%) lifted with maximum acceleration. Popularized by Westside Barbell/Louie Simmons. Advanced variations will use added bands or chains to increase the loading at the top of the range of motion.

These will all have a positive effect on increasing your power output. But how do they stack up compared to each other?

Power output

I’m sure that you will agree with me that if you are training for strength, the loading schemes/methods in which you can use the most weight will be the most effective. Using lighter weights can still help, without being the best. Doesn’t it stand to reason that the same would be true for power production? That is, the exercises/methods that lead to the largest power output will also be the most effective at increasing your capacity to produce power?

Of course, it does.

If we look at studies measuring the power output in the four methods listed above, we can find that two of them rank above the others when it comes to power production. One is very close and a last one is miles behind.

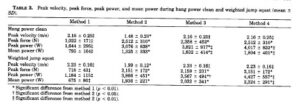

The power clean and the jump squat (with the proper weight) are on top when it comes to power production, with values typically in the 3200 – 4100 watts range. The jump squat actually seems to produce a bit more power than the Olympic lifts, but it’s close.

Note: The researchers found “method 2” to be the most accurate to measure power output.

From: Hori, Naruhiro, et al. “CLEAN AND THE WEIGHTED JUMP SQUAT.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 21.2 (2007): 314-320

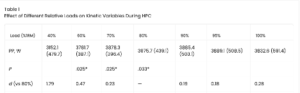

With the Olympic variations (at least the power clean) load actually doesn’t seem to matter that much when it comes to power production in competent individuals. Loads ranging from 70 to 100% all lead to a similar power output

From: Takei, S., Hirayama, K., & Okada, J. (2020). Is the Optimal Load for Maximal Power Output During Hang Power Cleans Submaximal?, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 15(1), 18-24.

However, for jump squats, loading plays a big role in the effectiveness of the movement. Using 30% of your maximum squat (1RM) leads to a much greater power production than 55 and 80%. It also leads to a lot more greater improvements in jumping and agility performance (McBride, Jeffrey M., et al. “The effect of heavy-vs. light-load jump squats on the development of strength, power, and speed.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 16.1 (2002): 75-82.).

Some other studies even found that 20% of your max squat to produce more power than 30%. So with loaded jumps squats, heavier is not better and you should not treat them like a progressive overload movement (trying to add weight over time).

The Olympic high pulls are in third position, but can actually be pretty close to the power clean if the appropriate load is used.

When the loads are lighter than 80% of your max power clean on high pulls you produce a little bit less power. But as you go to the 80-100% range, it is pretty much the same. Most people are 20% stronger on high pulls than power cleans, so high pulls with 60-80% of your power clean would be like power cleaning with 40-60% of your max. Which the previous study has shown produces inferior power output.

From: Takei, S., Hirayama, K., & Okada, J. (2020). Is the Optimal Load for Maximal Power Output During Hang Power Cleans Submaximal?, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 15(1), 18-24.

The speed squat is much lower in power production, even when using a load that allows you to produce more acceleration. Even with a load as low as 40% (which gives you more speed and acceleration), power production “only” reaches 2000 watts, much lower than our preceding methods (Hester, Garrett M., et al. “Power output during a high-volume power-oriented back squat protocol.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 28.10 (2014): 2801-2805.).

One caveat though. Very strong powerlifters, who are not skilled in the Olympic lifts, might have similar power production values in both because of the high loads they can use on their squats. That’s why the Westside guys who squat 700-1000lbs and use a bar weight of 500-600lbs can produce a very high power output (power is force x velocity). But the fact is that a “normal” athlete will not be able to use a heavy enough weight to match the power output of power cleans or jump squats.

Why? Because power is a combination of force and velocity (or distance divided by time). An athlete who uses 225lbs for speed squats will not be able to move twice as fast as a Westside guy who uses 600lbs. If both use the same percentage, they will move at around the same speed. The only way to compensate for a lighter load is to produce more velocity.

That is not to say that the speed squat is not effective. Power output is not the only thing that matters.

Other factors to consider

While the power output during an exercise is the primary factor for improving your capacity to produce power, there are other elements to consider when evaluating the value of a movement.

Let’s look at a few of them.

Technical complexity

The Olympic lift variations might come out on top (slightly) when it comes to power production, but not every coach is capable of teaching them correctly. While the simpler variations (power clean from the hang or blocks, power snatch from hang or blocks) are easier to learn and master at a sufficient level, they still require a few sessions with a qualified coach, or longer if you learn by yourself by watching instructional videos.

As such, an athlete might need a few weeks to reach a technical mastery level that is sufficient to use loads and speeds that lead to maximum power production.

The high pulls, especially high pulls from the hang or blocks can be learned more rapidly. However, from experience, people tend to pull with the arms too much and too early. It is important to learn to produce the speed with a violent leg, hip and trap action. The arms only pull once the bar has upward momentum.

While the high pulls are easier to learn than the Olympic lift variations, there is still a learning curve requiring a few workouts, depending on the individual.

Jump squats are easier to learn as it’s essentially the same movement pattern as a skill practiced by most athletes for years: vertical jumping. Obviously, the added load makes the movement a bit more complex and demanding, but nowhere near the extent of the previous two exercises.

The version with the bar on your shoulders (like in a squat) might not be ideal for someone learning the jump squat. He might opt for a version where you hold a DB on your chest, a DB in each hand to your side or perhaps use a trap bar.

Speed squats are the easiest to learn, especially if the athlete has experience with a regular squat (which he should before integrating any of these power exercises).

Depending on the motor skill of an athlete, how quickly he learns and your teaching skills as a coach, the “best” power movements in theory might not be your no.1 option.

The length of the off-season and the setting in which the athlete trains can also play a role: if you have a very short off-season period, requiring 2-3 weeks before an athlete can train a lift at a level that will give maximum power stimulation might not be acceptable.

If you are training athletes in a group setting by yourself, the more complex Olympic lifts can also not be ideal as you can’t teach and supervise everybody properly.

Finally, if you coach an athlete online (where it’s hard to give immediate feedback) coaching the Olympic lifts can be quite a challenge (it can be done if the athlete has some experience with them).

Pre-requisites

Another potentially limiting factor is the pre-requisites to be able to do the above power movements.

Some exercises require mastering less complex and related exercises, as well as having proper mobility.

Out of the four power exercises mentioned, the Olympic lift variations have the most pre-requisites.

Both the power clean and power snatch require that you master the back squat as well as Romanian deadlift (you need to know how to hinge properly) and they require proper mobility if they are to be done safely with good technique and proper positioning.

Both the clean and snatch require good thoracic mobility. Lack of hip flexor extensibility will also make it impossible to achieve a proper catch position (similar to an athletic position: hips back, chest up, knees at 90-100 degrees).

To do the power clean properly you also need to be able to have the bar on your shoulders with the elbows pointing forward while still holding the bar with a full grip and in the power snatch you need the shoulder mobility to hold the bar overhead behind the ear line while the torso is angled forward about 15-20 degrees.

A lot of athletes, especially bigger ones (like offensive and defensive linemen in American football or in rugby props/hookers) lack in the mobility department. Until they address these issues, the variations of the Olympic lifts are not your best option.

The speed squat does require the mobility to do a full squat (or at least a parallel squat) while staying in a solid position. For most athletes the potential limitations will be ankle mobility and hip flexor tightness. But it’s not as big of an issue as on the Olympic lifts, and if they are already squatting it is likely not a problem at all.

The high pulls, especially from the hang or blocks, do not have the same mobility requirements as the catch is where mobility is a bigger issue.

The jump squat is the least impacted by mobility as you don’t need to go to a full squat position and the landing doesn’t have the same requirements as the catch of a clean or snatch. However, you have other requirements when it comes to integrating loaded jump squats in your program: you need to be very efficient at jumping AND (especially) LANDING. An athlete will need to have been doing normal jumps extensively in his training before moving on to loaded jumps.

Side benefits

There are other benefits to some of the power exercises outside of a high power output. These can be important when deciding which one(s) to use.

Variations of the Olympic lifts: Trains the capacity to absorb force, but to reap the most out of this benefit you need to be able to catch the weights in an athletic position. Has positive effects on strength development, not just power (especially with higher percentages). Can help develop some upper body muscles (traps, back), especially with higher reps (4-6) done from the hang. Trains coordination between the upper and lower body.

High pulls: Very effective at building the traps and upper back, especially when done from the hang with sets of 4-6 reps. This can be important in contact sports. Can build strength, not just power especially when done with higher percentages. Also trains upper and lower body coordination.

Jump squats: Trains the body to absorb force if you focus on the landing as much as the projection.

Speed squats: Can help you improve squatting technique. Is a great introduction to power exercises. Can act as a “deload” from heavy squatting while still getting strength and power development.

So, Which One Is The Best?

As always, the answer is an underwhelming “it depends”.

It is my belief that if someone is technically efficient at them, the power variations of the Olympic lifts are the “power exercises” that give you the most bang for your buck. But if taught or performed poorly, they lose their effectiveness and can even be dangerous (especially if the athlete has mobility issues).

The high pulls are an interesting alternative to the Olympic lifts because technique and mobility are less of a limiting factor. But there is still some room for poor technique leading to losing most of the benefits when it comes to power development. Mostly overusing the arms, which is very common when learning this exercise.

The loaded jump squat will give you all of the required power gains and is actually more specific to jumping making it easier to transfer the gains in power to actual athletic movements. It is also easier to learn. As such, when training a large group of athletes, someone at a distance, or someone who has poor motor learning or a short off-season, jump squats might be your best option.

While the speed squat will absolutely improve power production capacity. I personally prefer to use it with lower-level athletes in combination with a jump progression to prepare the athletes for the more demanding power exercises. The combination of speed squats and jumps will give you the tools to do jump squats safely and effectively and can even transfer well to your capacity to learn and perform the power versions of the Olympic lifts.

Note on speed squats: I personally believe that an athlete should always try to accelerate his squats as much as possible, regardless of the load on the bar. Whether you have 40% or 100% your intent should be to be as violent as possible with the bar. This means that your warm-up sets are done with the same focus and drive as the work sets.

This means that the athletes I work with do “speed squats” all the time, even when it is not specifically planned.

Let’s say that they have 3 heavy work sets of 3-5 reps. Well, they will normally require 3 to 5 gradually heavier warm-up sets depending on their strength level. These 3-5 gradually heavier work sets would technically qualify as “speed squats” provided that you do them with the intent the kill the bar.

This dramatically improves the efficacy of your workout. Both by activating your nervous system and by training to move fast.

A recent study found something that I long ago knew by instinct: for athletic performance, how heavy you can lift with high acceleration is more important than how much you can lift.

The conclusion of the study was that: “ The bar-power outputs were more strongly associated with sprint-speed and power performance than the 1RM measures. Therefore, coaches and researchers can use the bar-power approach for athlete testing and monitoring. Due to the strong correlations presented, it is possible to infer that meaningful variations in bar-power production may also represent substantial changes in actual sport performance.”

From: Loturco, I., Suchomel, T., Bishop, C., Kobal, R., Pereira, L. A., & McGuigan, M. (2019). One-Repetition-Maximum Measures or Maximum Bar-Power Output: Which Is More Related to Sport Performance?, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 14(1), 33-37

I personally believe that how much weight an athlete can lift at a speed of 0.6m/s is more important than the heaviest weight someone can lift. Some people can lift their 80% at 0.6m/s others will only lift their 60% at 0.6m/s. The former will have a better athletic transfer.

Conclusion

It is my personal belief that the discussion about which lifting method is best to improve power production is kinda moot because you absolutely can use more than one method in the training of athletes. I certainly use all of the methods presented in this article.

However, some coaches, because of lack of experience with certain methods (Olympic lifts mostly) or lack of time need to select one or two approaches only. As you can see from this article, as long as your intent is to move as fast as possible, it all works pretty much equally well for improving power production.

Some methods will have minor side benefits, but likely not enough to make you miss out on something major.

The moral of the story, and yes this is underwhelming, is that if you perform “fast” lifting exercises (with the intent to be violently explosive) and include jumps and throws in an athlete’s program, it will make them more powerful. Period.