Knowledge

Partial Lifts, Full Results

Articles, Neurotyping, Strength and performance, Training

Partial Lifts, Full Results

The word that best describes me as a coach is “variation”. I love to experiment with any method I can find or come up with. If I have to stick with the same approach for more than a few weeks I get bored and lose focus. I believe that this might have hurt my personal progression over the years because I would get bored of something not when it stopped working, but when I understood its effect on the body (never reaping all the gains I could from a method). However, as a coach it really helped me because it allowed me to expand my toolbox significantly, which gives me a lot of weapons to fix issues I had with my clients.

But despite that need for variation, there are a few methods that I’ve always been drawn to and stuck with me for most of my “career” as a lifter then a coach. I can count these methods on the fingers of one hand:

– Isometrics

– Wave loading

– Clusters

– Rest/pause

– Partial lifts

These are my favorite go-to methods. They have always given me the best results, especially in the strength and performance category (a lot of people ignore that I started out as a strength coach, not a body composition specialist).

Out of all of these, the use of partial lifts remains the most mysterious and misapplied. For that reason, a lot of people don’t report a good transfer to full range lifts.

Let’s explore what partial lifts are, why they work, and how to use them to get results.

How do partial movements work?

Partial lifts have long been used by lifters seeking to increase strength. Even back in the 1800s, show strongmen resorted to partial lifts to impress the crowds (because they could lift more weight). They gained in popularity when power racks became common in gyms because the racks allowed a lifter to start the bar at various heights, reducing the range of motion. Anthony Ditillo was likely the guy who really popularized the use of heavy partials in training in the 70s. He is one of my strongest influences along with Doug Hepburn.

Partials are more typically associated with building strength. They consist of shortening the range of motion to allow you to either lift more weight than you can on the full-range movement or do more reps per set with a maximal load. Even today, they are very popular in powerlifting circles, especially those following the Conjugate system (Westside Barbell system), which relies heavily on partial movements (board presses, box squats, pin pulls).

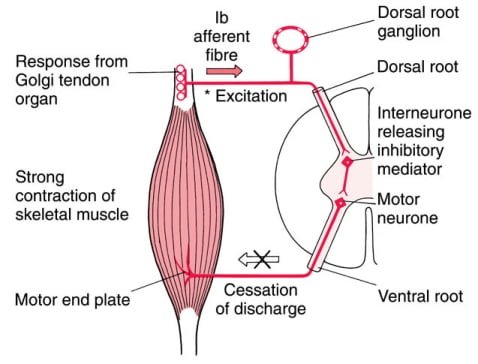

Partials work mostly by desensitizing the Golgi Tendon Organs (GTOs):

To make it simple, the GTOs’ function is to protect yourself against yourself. They are a protective mechanism that kicks in when the body senses that excessive force is about to be produced and that you risk tearing your muscle or tendon. The body will then inhibit force production, limiting how much weight you can lift.

The disadvantage of this mechanism is that it is overly protective: Normal, non-trained individuals are capable of using about 30% of their strength potential, while decently trained individuals may be capable of 60%, strength athletes, 70%, and world-class lifters 80-90%.

Heavy lifting desensitizes the GTOs. Essentially, repetitive bouts of heavy lifting “convince” the nervous system that your body can handle a higher force production without tearing itself apart. Of course, thickening of the tendons and building more muscle (especially at the distal portion) also desensitizes the GTOs.

Heavy partials allow you to put a great load on the muscles and tendons, and even though they are partial movements, the “sensation” of the tension remains similar to what happens in the full range of motion. Since you can use much more weight on a partial lift due to mechanical advantage, you can more effectively and rapidly desensitize the GTOs.

As such, once you have attained a certain level of lifting experience, muscle mass and strength, heavy partials when properly used, can rapidly increase strength.

There is also a psychological benefit to heavy partials: they get you used to handling supramaximal weights. Over time, this will make your maximum effort lifts feel lighter, which is definitely an advantage when testing your strength: many lifts are missed before the lift even starts simply because it feels heavy and intimidating.

Note that partials can also be used for bodybuilding purposes, by extending the time under tension. For example, once you achieve failure or close to it on the full-range movement, you will still be able to continue with a partial range of motion movements. Even though the full range is not being trained, you are still imposing more fatigue on the muscle fibres, which will lead to greater adaptations (more growth).

The Two Types Of Partial Lifts

There are essentially two broad categories of partial lifts:

1. Eccentric-Concentric: In this first category, you initiate each repetition with an eccentric phase prior to executing the concentric/lifting portion. For example, you would start a bench press at the top (like with a regular repetition), lower it halfway down (or another depth depending on the range of motion you want to train) then reverse the movement, lifting it back up to the starting position. In this version of partial lifts, you can do the movements “normally” while shortening the range of motion or using apparatus to shorten the range (e.g. boards/blocks for the bench press or a box for squats).

2. Concentric-Eccentric: In this second variation you initiate the movement with the concentric action and then lower the bar back down. Here, we typically refer to lifts from pins. For example, bench pressing inside the power rack, with the bar set on safety pins using a partial range of motion; or deadlift with the bar starting below the knees.

The first option obviously has a greater transfer to lifts that starts with an eccentric phase (bench press, squat), while the second one is better suited for lifts that start with the concentric portion (deadlift, chin-ups, military press).

Using the concentric-eccentric method for the bench press (or squat) can still give you strength gains, mostly via desensitisation of the GTOs, but these gains will not as readily transfer to an increase in performance on the main lift, mostly because it does not train the transition from eccentric to concentric that is a key portion of the bench press and squat. If you do decide to use partial lifts from pins (concentric-eccentric) for the bench press or squat, you will need to include a form of bench pressing (close-grip, decline, incline, DB press) that trains the transition between the eccentric/lowering phase and the concentric/lifting phase. This would normally be your main lift of the workout, with the part being the secondary exercise. For example:

A. Close-grip bench press

5 x 5

B. Top-half bench press from pins

Work up to a 5RM

To make the transfer even more efficient, you could use as an assistance exercise a movement using the 1 & 1/2 technique in order to better train the eccentric-concentric transition. For example:

A. Close-grip bench press

5 x 5

B. Top-half bench press from pins

Work up to a 5RM

C. DB bench press

1 & 1/2 technique (lower all the way down, lift halfway up, lower back down, lifting completely = ONE rep)

3 x 6

A lot of people report very little transfer from partial lifts because they expect the gains to be automatic. If you don’t train all phases of the lift (eccentric, eccentric-to-concentric transition, concentric), you will not progress quickly on the movement.

Maximal, Supra-Maximal And Sub-Maximal Partials

There are variations of the two main categories of partial lifts. They relate mostly to the intensity zone being trained, which has a direct impact on the purpose and effect of the partials.

There are three intensity zones with partials:

1. Sub-maximal: These are partials done with a resistance that is less than 90-100% of your maximum on a lift. They are more often used to extend the muscle(s) time under tension during a set, which is mostly done for hypertrophy purposes, as a form of pre-fatigue to better focus on one muscle in a big lift, to strengthen tendons or to improve the technique of a specific portion of the range of motion. Here’s an example of each of these four applications:

a) Extending the TUT: After having done 6 reps on full range back squats, you finish the set by adding 4-6 half squats.

b) As pre-fatigue: Starting a set of close-grip bench press with 5 top-half reps before doing 4-6 full range reps to increase triceps involvement in the movement.

c) To strengthen tendons: Doing sets of a high number (20-30+) of bottom half partial on the DB bench press to strengthen the tendons and the distal portion of the pectoral and anterior deltoid muscles.

d) To improve the technique of a specific portion of a lift: Doing “floor to knees” on the deadlift. 5-10 reps doing only the first pull, focusing on precision and maintaining an optimal lifting posture and tightness.

2. Maximal: Using a weight that is your maximal performance, or close (slightly below or slightly above) to it (95-105%) on the full range lift for multiple reps on partial movements. The vast majority of the time, you will use anywhere between the last 3/4 to the last 1/4 of the movement. You can use either the concentric-eccentric method or the eccentric-concentric one depending on the lift you are training. I like this approach specifically to prepare the body to handle a specific load. It is especially effective when using a strength-skill approach for the full range movement (lots of work in the 75-85% range without going higher than an 8 RPE). For example:

PHASE 1 – 3 weeks

A. Deadlift

5 x 5 @ 75%

B. Pin pull from just above the knees

2 x max reps at 102.5 – 105% (goal for the end of the cycle) of the full range lift

PHASE 2 – 3 weeks

6 x 4 @ 80%

B. Pin pull from the knees

2 x max reps at 102.5 – 105% (goal for the end of the cycle) of the full range lift

PHASE 3 – 3 weeks

A. Deadlift

7 x 3 @ 85%

B. Pin pull from just below the knees

2 x max reps at 102.5 – 105% (goal for the end of the cycle) of the full range lift

It can also be used to increase heavy strength endurance: the capacity to maintain maximum force production for longer. This capacity is really useful when you are lifting a maximal weight in competition (or a test) and you have to grind a weight up. When you have to grind, you must maintain maximum force output for longer (because the bar goes up slowly) and partial lifts with 92-100% of your maximum for multiple reps increase your capacity to produce maximum force for a longer period of time.

3. Supra-maximal: This is the intensity zone most commonly associated with partial lifts. You are shortening the range of motion of the exercise to be able to use significantly more than your 1RM on the full range lift. A lot of people (myself included many years ago) recommended going as heavy as possible on those partials, often doing 1-3 reps per set. But ideally, you should avoid using more than 120% of your maximum, because anything higher than that is not necessary to get maximum GTO desensitization (which is the main benefit of supra-maximal partials) and increases the risk of injury while also changing the technique used which could lead to less transfer to the full range lift. It’s best to stay in the 110-120% range and do up to 5 reps per set, working up to a 5RM being a very good approach with supramaximal partials. If that 5RM ends up being higher than 120% of the full range lift, increase the range of motion.

When I did my strongest bench press (445lbs), a large part of my training was performed on partial lifts. My favorite combination was supramaximal bench pressing from pins with explosive full range cambered bar (or Duffalo bar) bench press or explosive dips. It always gave me rapid strength gains within 3-4 weeks.

Why Some People Are Not Improving With Partial Lifts

I’m a huge believer in partial lifts. They have always delivered for me and for the people I worked with. Yet many people have tried them sometimes with underwhelming results. Here are the main reasons why some people are not getting a lot of full range gains from partial lifts:

1. They are using the wrong type: As I mentioned, in lifts where there is an eccentric phase preceding the concentric (squat, bench press) it will be much harder to transfer partial gains to the full range if the partials you do are from pins. You can get a positive transfer if you include work to emphasize the eccentric-concentric transition, but by itself it will not lead to great full range results, at least not directly. Board presses and box squats will yield better results, at least in the short term than bench and squat from pins. Partial movements done as if you were doing full lifts (a regular movement but going down halfway for example) is also a good option.

2. They are not using the same mechanics as in the full lift: This is very common. People will use different body positions and mechanics during partial lifts than in the full range movement, mostly to give themselves a more advantageous leverage (this is more common on pin pulls). But if you do that, the transfer to the full range lift will be minimal. You might even have a negative transfer due to improper motor learning. I suggest filming yourself when doing partials to see if your mechanics are the same as when you do the full lift.

3. They are using too much weight: One of the main benefits of partial movements is to load more than in the full range lift. When you do that you desensitize the GTOs more rapidly. But more is not always better. There is no real benefit from going above 120% of your maximum when doing partial lifts. If you can do more than 120%, increase the range of motion or increase the reps. Adding more weight will simply cause more CNS fatigue, increase the risk of injuries and increase the likelihood of changing the lifting mechanics.

4. Not enough time under load: Strength work doesn’t require the same time under load as hypertrophy work (20-60 seconds), but to maximize development you still need to be under load for a certain period of time. This is both for neural improvements and muscle fiber adaptations. For fiber adaptation to occur you need to fatigue the recruited fibers. As Zatsiorsky wrote, a muscle fiber that was recruited but not fatigued is not being trained. If you do a single rep on a partial movement, the load will be very high but the time under load will be minimal, maybe 1.5-2 seconds. That is not enough to cause structural changes to the muscle fibers. Furthermore, during a full range maximum effort lift you will be under load for a certain period of time. If during your partial work your muscles are under load for less than the duration of a max effort full range lift, it will not improve performance much. At the very least, you need 2-3 partial reps to be under load for the same duration as a max effort lift, and likely 4-5 to get some fiber adaptations.

5. Not the right approach for your neurotype: Type 1B will not get a great benefit from partial lifts from pins or even on things like board presses and box squats. In fact, for them lifts from pins might be more dangerous because they will try to yank the bar off of the pins causing a very large shock on the tendons. That’s because their natural strategy is to use the stretch reflex. For them, a better option is to do “regular lifts” with a shorted range of motion (e.g. squat going halfway down), this will allow them to use the stretch reflex to initiate the transition between eccentric and concentric. That same approach will not work as well for a Type 1A.

6. Too much volume: Heavy partials are addictive because you can move tons of weight. But it comes at a price: the more force your produce the more you amp up/excite the nervous system. The more excited the CNS is (neurons firing faster), the harder it is to bring it back down after the workout is over. The longer your CNS stays amped up after the sessions, the more CNS fatigue you create and the longer it will take to recover from that session. This is especially true with people who have low serotonin and/or GABA, since they will have a harder time calming down their nervous system once it was excited. If you are someone with a higher anxiety level/less serotonin or GABA, you can really hurt your progressing by doing too much supra-maximal or maximal partial work.

7. Neglecting full range work: Even when you use the right version of partial work for your needs, you still need to train the full range on that movement pattern. I’ve tried to do exclusively lifts from pins for 6 weeks and although my bench press from pins went up significantly (from 385 to 435 on bench press from pins from 2″ from the chest and from 405 to 485 on top-half partials), my regular bench press didn’t go up at all. But every time I kept using an exercise (not necessarily the bench press, squat or deadlift itself) to train that eccentric-to-concentric transition on the movement pattern, my full lift increased. I like a conjugate approach here: not using the actual lift when training the full range and changing the exercise every 1-2 weeks.

8. Using them when you are not ready: This is a cardinal sin when it comes to all advanced methods: chains, bands, weight releasers, partials, clusters, plyometrics, etc. They work great if you have built a foundation first. What do I mean by a foundation? I mean that you have added a significant amount of muscle mass and strength via traditional methods, you have developed a high level of technical efficiency on the big lifts (if not, you won’t be able to maintain proper mechanics when doing partials) and you have strengthened your tendons. I personally see no point in using heavy partials if you can’t bench press at least 1.75x, squat 2.25x and deadlift 2.75x your body weight. There will be exceptions (like with everything), but this is normally pretty accurate. OF COURSE, I’m talking about supra-maximal partials here. The submaximal and even maximal versions can likely be used sooner.

Conclusion

Properly done partial lifting is one of the most powerful methods I know. It is an advanced method though, so not everybody should use it, but when used properly by the right person it can deliver very rapid gains in strength. It can also be adapted to hypertrophy training and even technique work. A great tool to add to your toolbox!