Knowledge

How To Keep Muscle During A Layoff

Articles, Muscle gain, Training

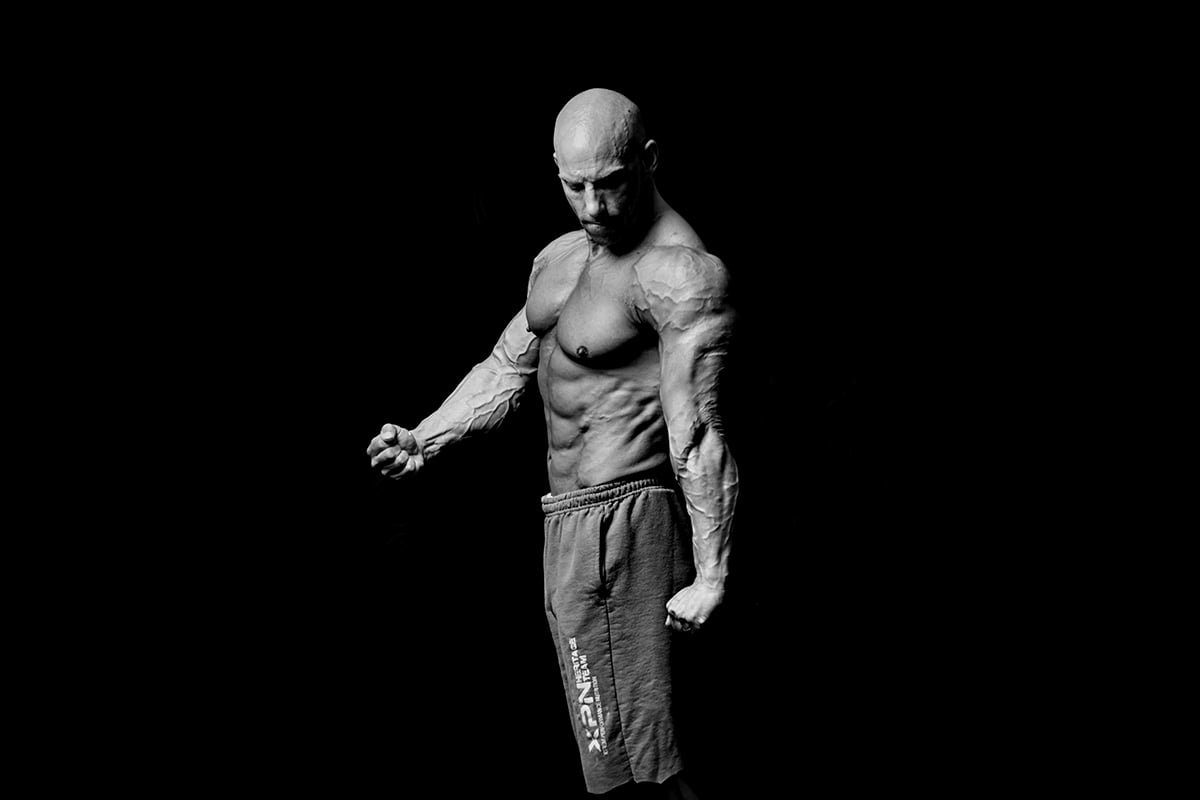

How To keep Muscle During A Layoff

Here’s What You Need To Know…

- Don’t panic. You won’t lose muscle if you take a week off from training.

- After a three-week break, you might lose 5-10% of your strength mostly due to lost neural adaptations.

- After three weeks, it’s possible to lose muscle mass, but there are ways to mitigate the loss.

- You don’t gain strength by deloading. You reveal the strength you gained during your hard training cycle. Fatigue masks fitness. Deloads reveal it.

- People notice overtraining when they start to lose strength and body weight, so their normal reaction is to train more, making things worse.

Time Off: Planned And Unplanned

There are three situations where a serious lifter would take time off from training:

- A planned deload to help reach peak performance or to recover from overtraining.

- A short planned break (vacation or trip).

- An unplanned layoff (sickness or injury).

Deloading and hiatuses from training are part of everybody’s life. While it’s my job to help people get the most out of their training, it’s also part of my job to help them retain most of their gains when they’re forced out of the gym.

Here’s My Take On All Three:

A Planned Deload

Deloading prior to a competition or before trying to hit a new PR.

It’s a common approach to include a deloading period prior to a competition or “gym test.” The theory is that you impose large stress on your body with 2-3 weeks of hard training, then you include 4-10 days of reduced training or active rest. This is called a taper.

During the taper, several markers of performance go up:

- Testosterone peaks (it’s normal for it to get low during high-stress training).

- The nervous system gets back to optimal function (as evidenced by a marked increase in grip strength tests 3-4 days into the taper).

- Super-compensation of glycogen stores occur and the body stores more water inside muscles and less subcutaneously (possibly indicative of lower cortisol).

You’re left with a body that’s primed to function at its best. You don’t gain extra strength by tapering/deloading for a peak.

You’re simply revealing the strength you gained during your hard training cycle. Fatigue masks fitness.

When you accumulate a certain degree of systemic fatigue, you might only be able to function at 90 or even 80% of what you’re capable of. The thing is, once you’re past the beginner stage, you must train at a level that will cause some accumulated fatigue to stimulate further gains in strength and size, and the harder you train to make gains, the more fatigue you build up.

So, during a hard cycle, you might be able to gradually add some weight to the bar (making you believe that you aren’t plagued by fatigue), but the results you see in the gym and in your body are inferior to the real gains you’re making because fatigue masks your true level of fitness.

So, why not avoid accumulated fatigue altogether?

If you’re training hard enough to get optimal gains it will lead to a certain level of accumulated fatigue. If you aren’t building up a certain level of fatigue, then you aren’t imposing a stimulus strong enough to force the body to adapt.

Important: Don’t stop lifting during a taper. Sure, not training at all will help you recover faster, but it would be at the expense of timing and neural activation.

When I competed in Olympic lifting, I performed the most poorly when my coach had me do a taper where I wouldn’t train at all 4-5 days prior to the competition. I lacked timing and felt out of the groove and not fully focused.

Don’t spend more than one day without touching a bar when trying to maximize performance, even if it’s only light training to stay in the groove.

Application: During the taper, we do the following:

- Drop all assistance work, only doing the 3 main lifts.

- Drop training frequency to 3 times during the week: Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and test on Saturday.

- Perform the 3 lifts at each session, using submaximal weights.

-

- Monday: 70% for 3 sets of 3

- Tuesday: 90% for 3 sets of 1

- Thursday: 80% for 3 sets of 2

- Saturday: Test

- Increase caloric intake by about 25%.

Most people make the mistake of decreasing calories when they taper. They think that since they’re training less, they need less fuel. They’re also afraid of gaining some fat if they eat more while training less.

This is the best way to miss your peak! The goal of the taper is to get rid of any fatigue you might have that could mask your fitness. By eating less you risk slowing down your recovery.

Deloading To Recover From Overtraining

A certain amount of accumulated fatigue is normal when training hard toward a goal, but we don’t want this to turn into an overtraining situation. When it happens you need to get out of that state as soon as possible.

Most people only notice “overtraining” when they start to lose strength and body weight (they also feel smaller and softer due to an increase in cortisol), so their normal reaction is to train more to kick-start the gains. But that will only make things worse.

Sometimes you need to get some real rest and get the body ready to train hard again, and that’s often the hardest thing to do. Depending on the amount of accumulated fatigue, you might need 1-3 weeks of reduced training or even full rest to get back to normal.

You’ll need to normalize hormone levels (testosterone to cortisol ratio mostly), reduce inflammation, and restore glycogen. When I face an athlete in that situation, I use a very aggressive approach because most of them don’t have the luxury of taking a lot of time off.

Real-life example: I work with a lot of CrossFitters. Last year one of them got into a severe overtraining state right as the Open started.

For those who don’t know, the Open is where you qualify for the Regional championships and eventually the CrossFit Games. It’s a series of 5 WODs, one per week for 5 weeks. If you don’t finish in the top 48 in your region, you can’t qualify for Regionals.

This individual had a great season at first, winning a few big competitions and getting in some pretty badass lifts, but right at the key moment of the season, she failed to finish her normal workout and sometimes started crying during subsequent sessions.

She started the Open dismally, not placing anywhere close to a qualifying spot. I told her to stop training altogether and only do the one competition WOD for the week.

She started to feel much better. During the 2 weeks prior to the Regionals, she got back into training, but we used micro-sessions: 15-20 minute workouts. We also continued with the supplementation protocol. Five days prior to the Regionals, she beat her personal best on the clean (235 pounds) and ended up placing 4th.

Application: When you’ve reached a true state of overtraining, it might take up to 4-5 weeks to get back into full form. In most cases, you’ll be good to go in 2 weeks.

Still, this is unsettling for most people since they’re afraid of slipping backward if they drastically reduce their training. Not so! In fact, they might slip backward if they keep training!

Recommendations for someone on the brink of disaster:

Stop hard training for one week. This will allow you to restore an optimal hormonal milieu, get rid of the chronic inflammation, replenish neurotransmitter levels, and restore glycogen stores. Sure, it might make the nervous system more sluggish, but in your case, the priority is to get your body back to normal fast, not to peak.

Protein pulsing has an anabolic effect, and it’s not simply due to having more protein available. Rapidly going from low to very high blood amino acid levels stimulates protein synthesis, so during a period of detraining, you can maximize your chances of maintaining your muscle mass by using protein pulses. In cases of severe chronic fatigue, have 5 or 6 pulses during the day, but most importantly one first thing in the morning, one right before bed (ideally with the last solid meal being about 2 hours prior), and another pulse in the middle of the night if you wake up to pee. The faster you are when you take the pulse in, the more pronounced the effect.

Start training again after a week of rest. Use short sessions, 20 minutes or so. Try to do one every day. The reps should be low and the weight submaximal (70-85%). Do a minimal volume of work. I like to do only one exercise per day for 5 sets of 3-5 reps. Create minimal fatigue and activate the nervous system. Get back in the groove.

After the week of rest and a week of low volume training, most people will be good to go and can resume regular training. Some, however, might need one more week of reduced training. If you even have to ask yourself, “Do I need one more week of reduced training?” the answer is always yes. Better to err on the side of caution.

A Short And Planned Break

While I’ve worked with a lot of pro and high-level amateur athletes and bodybuilders in my career, I also work with average Joes.

They often have to interrupt their training for 1-3 weeks because they’re going on vacation or on a work assignment. Invariably, they’re all afraid of losing strength and size while away from training. Here are some observations from years of in-the-trenches experience:

Unless you’re tied to a hospital bed, you won’t lose any muscle mass if you take a week off from training. You’ll feel smaller and more flat. But it’s not because you’re losing muscle mass. It’s because your muscle tone is decreasing slightly due to the nervous system is a bit less “turned on.” You also get rid of chronic inflammation in the tendons and muscles, both of which make the muscles look swollen, larger, and tighter. If the muscles feel “looser” and less swollen, it’s easy to make the mistake of believing that they’re smaller, but they aren’t.

You might lose a small amount of muscle mass if you’re away from training for two weeks, but it’s not enough to make a big difference. Any lost muscle is quickly regained when you get back to training. My client who went away for 3 weeks looked a little bit “deflated” when he came back, but after one full week of training, he looked like he did before the trip.

When it comes to strength, losses can be a bit more rapid, but it’s simply because you lose some neural efficiency. If you take two weeks off, you might lose a significant amount of neural efficiency so your strength might decrease a bit (5% or so, 10% for some). Don’t panic about that because it’ll come back to its previous levels within 2 weeks of resuming training.

When I know a client will have to miss training for 1-3 weeks, we’ll do a training blitz right before the vacation. For 1-3 weeks (normally I do the blitz for the same length of time as the vacation), I amp up the training stress significantly. This means increasing the overall training volume by at least 50%. This can either be done by increasing the number of sets per exercise or the number of training sessions per week. Intensity (amount of weight lifted) remains about the same despite the increase in volume. The goal is to create a state of accumulated fatigue so that during the vacation the body recovers from the previous stress instead of detraining and regressing.

Application: If you have a planned lay-off from training coming up, increase the training volume by about 50% while maintaining training intensity. This will create a state of accumulated fatigue and during the off period the body will spend more time recovering and less time detraining. I like a 1:1 ratio of stress week to off weeks.

An Unplanned Layoff

It could be illness, injury, or an unexpected event that makes it impossible to get to the gym. But all lifters are left wondering:

How much will I lose?

This is an individual thing. The longer it took you to attain your current level, the longer your gains will stay with you.

If you’ve been hitting the weights hard for 10 plus years, and have built a very stable foundation of strength and size, it will stay with you a lot longer than if you built your physique over one year. Gains made quickly are lost quickly.

Example: A former Canadian champion in Olympic lifting trained hard for about 15-20 years non-stop. At one point he was forced to take some time off from training (a career in the military and a very large family).

He stopped training for 5 years or so. When he got back into it, it only took him 2 or 3 months until his strength was back up to 90% of previous levels.

On the other end of the spectrum, one of my clients trained hard for a year and then stopped training for 8 months.

He lost 40% of his strength and about 10 pounds of muscle during that 8 months, which is very fast, and it took him 7 months to reach and exceed his previous level.

Young lifters who go on a cycle of steroids gain 20 pounds in a few months and lose everything they gained after they stop training for just a month. The gains came so fast that they hadn’t stabilized.

Another factor relates to the type of training you do. The more “neural” your training is, the faster you lose strength. For example, if you’re training almost exclusively with sets of 1-3 reps, you’ll lose strength more rapidly than someone who trains mostly with higher reps.

The strength gains achieved through lower reps are largely due to neural factors, which are lost quickly, while gains achieved through higher reps are more stable. How much strength and size is lost will also depend on what you do during your forced layoff.

If you’re physically active and keep doing the right things in the kitchen, then you’ll preserve more strength and size than if you become completely sedentary and eat crap.

As a rule of thumb, you won’t lose any strength or size from a one-week layoff. You might feel more flat after 4-5 days, but that has nothing to do with muscle loss – just a decrease in muscular inflammation, a decrease in myogenic tone, and maybe a lower level of intramuscular glycogen.

After a layoff of 2-3 weeks, you might lose 5-10% of your strength, but you won’t be losing much muscle mass, and the loss of strength will be mostly due to lost neural adaptations. Once you go past 3 weeks, it’s possible to lose muscle mass, but the rate at which you lose it is highly variable.

Most serious lifters will definitely start to lose some muscle mass between the third and sixth week of detraining.

There will be a significant loss in muscle mass in most individuals after 12 weeks. Although it’s not scientific, most of my hockey players lose roughly 10 pounds of muscle mass during a season.

Keep in mind that we’re talking about a period of approximately 7 months, but they’re all generally doing some maintenance work once a week and they’re keeping active by playing hockey.

That’s roughly equivalent to a lifter not training at all for 3 months, so losses of 6-10 pounds of muscle during a 3-month layoff is what you can expect if you don’t try to use the proper strategy to hold on to muscle.

If your break lasts 1-3 weeks and you remain somewhat active, you shouldn’t lose much muscle, if any. You might feel more flat, smaller, and softer, but that won’t be due to a decrease in muscle mass.

If you’re forced to stop training for 3-6 weeks you’ll start to lose some muscle, but how much can depend on what you do to prevent excessive losses.

Past the 6 week mark and you’re bound to lose a significant amount of gains regardless of what you do, but the good news is that it’s easier to regain lost muscle than it is to build it in the first place.

How Quickly Will I Gain It Back?

This is highly variable, but it will take you less time to regain lost muscle than it took you to build it in the first place.

While there’s no set rule as to how fast we regain lost muscle, think in terms of a 1 to 1-time frame: It’ll require about the same time to rebuild the lost muscle as the duration of the detraining period.

If you were away from training for 6 weeks, you should go back to your previous level of development and performance within 6 weeks of resuming hard training.

What Can I Do To Cut My Losses?

A big mistake: when people have to stop training, they also stop doing all the other things they were doing to maximize their gains while training.

They stop eating a muscle-friendly diet and often even start to eat more and more crap and less nutritious food; they go to bed later, get less sleep; become less physically active; and stop using supplements.

Their logic is that all those healthful things they do outside the gym are to enhance their training, but if they’re not training, what’s the point? They’ll start to do things right when they get back in the gym, right?

But if you behave this way you’ll lose muscle even faster. And you’ll probably gain some fat in the process, making it more difficult to get back into shape.

The things that help you gain more muscle and get leaner while you train are the same things that will help stave off muscle loss and fat gain when you’re forced away from training.

Keep doing all the good things you were doing to speed up your gains.

If possible, try to be even more diligent with the things you can still do to improve your body – follow a more solid nutrition plan, get plenty of rest, do more physical activity, and keep using some supplements that will help you retain your muscle mass.

Suggestions

Take any opportunity to train that you can, even if it’s only once a week or even once every two weeks. Heck, even 10 minutes is better than doing nothing. If you can’t train due to lack of time, try to fit in one single session every now and then. Every little bit counts to preserve muscle mass. If you’re injured, try to find what movements you can do. Some people think that if they can’t train as hard as they want, then it’s a waste. Nothing is a waste! Sure, you might not make any gains, but every bit of preserved muscle is worth the effort.

Keep fat gain at bay. If you aren’t training, chances are that you won’t need as many calories as you normally do. Keep a stable protein intake (if you decrease it, you risk losing some muscle) and reduce carbs and/or fat to maintain your degree of leanness or even get a little bit leaner. Getting a better body is about being muscular and lean. If you can’t get more muscular because you can’t train, you might as well work on the other part of the equation!

Stay active. Look for things to do like walking, sprints, jumps, or carrying stuff at home. If you’re in the mindset of trying to do as many things with your body as possible, you’ll start to see many opportunities all around you without having to go out of your way to do them.

Stay intellectually involved in your training – read articles and books about training. Take the off time to assess yourself and design a good training plan for your return. These things will help you stay motivated. And during a break, you can take a step back and have a more objective view of yourself, your body, and what you need to reach your training goals.

-CT