Knowledge

3 Phases For Retraining Overhead Movement

Articles, Rehab, mobility & injury prevention

3 Phases For Retraining Overhead Movement

Shoulder dysfunction is commonplace in training, particularly for overhead movement. While the structural diagnosis may vary: tendonitis, bursitis, subacromial impingement, sprains, strains, tears, dislocations, subluxations; the functional diagnosis is usually quite similar.

The functional diagnosis is the reason or causes for the pain. In other words, the dysfunction or compensation that has inevitably led to tissue injury, the structural diagnosis. But the reverse is also true. The functional diagnosis can be the dysfunction or compensation that occurs secondary to protection and inhibition due to the injury.

As trainers, we work with a functional diagnosis, and ideally, we work in collaboration with the health care provider who treats the structural diagnosis. This is important because you need to know what the diagnosis-specific contra-indications are with regards to movement. These may be different from one injury to another.

When intervening on a functional diagnosis, you will use categories of exercises that are independent of which tissues are problematic, and then select specific exercises that respect any restrictions or temporary limitations as indicated by the structural diagnosis. Let’s take our shoulder example.

Whether the injury was a dislocation or tendinitis, in most cases there will be the presence of scapular dyskinesis (abnormal motion of the scapula). So, whether an individual has shoulder impingement or a rotator cuff tear, they will get some type of scapular stability exercise.

Sometimes, there isn’t even a structural diagnosis. People often come to me with just plain shoulder “dysfunction”. They fill limited in overhead motion, they feel “congested” in the upper traps and cervical spine, they feel “pinching” in the back of the shoulder during overhead movement.

On assessment, I would say almost all of these cases have some degree of scapular dyskinesis. So, their functional intervention also includes (begins with, actually) scapular stability and reeducation. I imagine your next question might be: “Wait…so everyone with shoulder problems gets the same exercises?”

The answer is yes and no. They will get the same categories of exercises. While some may be the same, some will differ. As mentioned earlier, you will select specific exercises based on the restrictions or temporary limitations indicated by the structural diagnosis

If the structural diagnosis is subacromial impingement, you would avoid selecting exercises that are done overhead. If is it tendonitis, you might use isometrics to limit repetitive motion. This is how you strategize your intervention.

I generally use 3 phases for retraining overhead movement, which will be described in detail further, but first let’s go through some general considerations.

General Considerations For Overhead Movement

We’ve already discussed the fact that outside of the acute injury, problems at the shoulder (meaning the actual glenohumeral joint) usually have nothing to do with the joint itself. Specifically, limited end range shoulder flexion usually has little to do with the GH joint and a lot to do with the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine.

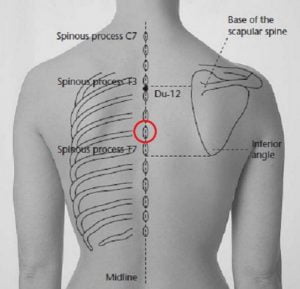

Shoulder movement involves movement of the thoracic spine all the way down to T6:

Full bilateral shoulder flexion requires thoracic spine extension. If moving just one shoulder into flexion, you require thoracic extension as well as rotation towards the same side. As such, you should consider the need for T-spine extension and rotation mobility work when intervening on the shoulder complex for optimal overhead movement.

Here’s a great mobility drill that targets both extension and rotation:

If having the hands behind the head is problematic, you might use a more classic drill like the sidelying T-spine rotation:

When managing the cervical spine, think upper cervical mobility and lower cervical (junction of C-spine and T-spine) stability. Supine chin tucks and seated chin tucks work well here:

Make sure rotation is happening from an axis running through the ears. Keep the teeth together.

Phase 1 – Neural Programming

Proper shoulder function requires proper scapular function. As such, the goal of the first phase is to improve the capacity to recruit the scapular musculature. It’s pretty much like working on the mind-muscle connection, but rather than focusing on specific muscles in this phase, the focus should be on understanding and accessing scapular movement, beginning with scapular retraction.

Because a common compensation is a substitution of the upper trapezius (early or excessive shrugging during retraction), exercises that combine depression with retraction often work quite well. This step comes first because the lowered irritability threshold of the upper trapezius causes it to be readily activated with any upper extremity movement. These exercises help down-regulate the upper trapezius to set the stage for the next steps of the intervention.

I typically use open kinetic chain exercises (OKC) in this phase, because I generally find that visualizing and accessing the various scapular movements is easier for most people in an OKC setting. I also find that people understand the multiplanar motion of the scapulae better when exploring OKC movement.

Without going into too much detail, as it is beyond the scope if this article, we should bear in mind that in certain cases of rotator cuff injury, you may need to avoid OKC exercises (they may even be contra-indicated in certain cases or stages of rehab).

OKC exercises of the upper extremity require appropriate rotator cuff stabilization to prevent excessive translation of the humeral head, something closed kinetic chain exercises, on the other hand, help limit. And before you jump the gun and decide to strengthen the rotator cuff using external rotation exercises, note that intervention to normalize scapular movement should precede attempting to load the rotator cuff.

Holding the arm elevated in front, to the side or overhead in standing is more difficult, especially with a load, and should generally be used at the tail end of Phase 1.

Here are 2 exercises I find have proved the be very effective in this stage:

Press the forehead into the forearms and pull the elbows down towards the sides. Don’t squeeze the scapuale together, pull them down.

Peel the shoulders off the ground, don’t hyperextend down to the lower back. Reach the fingers towards the heels sliding the scapulae down.

Phase 2 – Intensification

This is the phase where I start to introduce closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises and/or movements where the shoulder complex is bearing some of the weight of the body. In the early phases, you might have the individual inclined at a wall, progress them towards a bench, and then to a full push-up position.

Earlier in this phase, the focus remains on scapular motion, specifically on accessing and controlling it in CKC positions/ exercises. Think about the focus on the feet for squatting and deadlifting (“screw the feet”, “spread the floor”) and what that creates in the hips. The same goes for the hands vs the shoulders.

Here are some examples of exercises for accessing and controlling scapular motion in a closed chain setting:

Imagine you are screwing the hands into the wall, clockwise focus on scapular depression and downward rotation and counter-clockwise focus on scapular elevation and upward rotation.

Press into the wall with the forearms as you roll-up.

Later in the phase, I start to progress towards the overhead movement. With overhead work, most of the problems I see have to do with people trying to stabilize with the pressing muscles vs the pulling muscles. Let me explain.

If you don’t have the mobility and stability required to get the load vertical, you will try to get under it so that you can “press” it up. You see this where people hyperextend through the lower spine to get under the load.

I choose exercises to target maintaining stability at various degrees of flexion. One example is the wall walk-out, which can later be performed in the push-up position as a progression.

Phase 3 – Acquisition

In the acquisition phase, I start to progress the individual back towards full overhead pressing. There’s a lot of flexibility here and the exercises you choose will depend largely on the client. Essentially, you need to get them into positions where they can’t cheat.

For example, if they tended to hyperextend at the lower spine, that compensatory pattern won’t have disappeared just because you’ve now improved their overhead mobility. Starting them in half-kneeling or tall kneeling positions for pressing helps prevent this. I find alternating presses work well too, one-shoulder pressing while the other one remains racked:

Putting It All Together

Phases 1 and 2 typically last anywhere from 2 to 4 weeks depending on the individual, the key being the frequency of practice. Because these are low-intensity re-patterning and re-programming exercises, they need to be done aton. For sure, you cannot expect to go for only 2 weeks if they are not performing the exercises every single day.

If you’re in any way doubtful that they will be diligent enough, definitely go for 4 weeks. I have only seen good progress after 2 weeks in clients who were assiduous and performed their exercises once or twice a day.

In closing, remember that guidelines are always meant to be just that. In repatterning, the key is to make it meaningful for the client, so select exercises that best meet these needs.

-MLD