Knowledge

10 Things I Learned From Master Poliquin

Miscellaneous

10 Things I Learned From Master Poliquin

As I’m writing this article, I learned of the passing of my mentor Charles Poliquin a few days ago. It was a complete shock, you never think that monuments can die.

Charles was a true pioneer. He is responsible for more innovation than any other strength coach, has influenced more trainers than anybody ever did and really pushed training into the future. He was truly ahead of his time.

He had a polarizing personality. He was confident, driven, needed to be the leader, impatient and emotional. Because of that you either loved him or hated him. But even if you hated him, and didn’t agree with everything he said, you must admit that he did more for the advancement of training than all of his haters combined.

I was not always in agreement with Charles. In fact, one day we were talking, and he was kinda pissed at me for producing the neurotyping course, which gave a different interpretation than his system, and I told him: “Charles, I can promise you two things: we will not always agree on everything, but I will never disrespect you”. And we were good again.

Since he was my biggest influence, I decided to share some of the things I learned from him. Some of these things might seem basic now, but they truly changed the game 15-20 years ago.

Training Related

- Clusters

Almost 20 years ago, I was at a seminar given by Charles. I was still an Olympic lifter (or trying to be one) at the time, and I asked him what was the best way to rapidly gain strength.

“Cluster sets” was his answer. He then explained what they were:

“Pick a weight you can normally use for three reps and do 5 reps with it”.

Okkkkaaayyy… how do I do that exactly? If it’s a weight I can lift 3 times how can I get 5 with it?

“You rest 10-20 seconds between every rep, racking the weight after each one”.

Simple.

But however simple it was, it turned out to be the most effective training method I’ve ever used to rapidly boost strength. It’s what made me pass the 405lbs barrier on the bench press and front squat and the 500lbs one on the back squat.

Clusters likely have the strongest neurological impact of all the training methods I’ve used, save for maxing out (which you shouldn’t do too often). You also create more fatigue on the fast twitch fibers and as Professor Zatsiorsky wrote, “a muscle fiber that is recruited, but not fatigued, is not being trained”.

As such, clusters don’t simply improve the neurological factors involved in force production, but they also stimulate significant muscle growth, especially in the advanced lifter.

When I started using clusters I was using up to 5 work sets. It worked because I was young and had a very resilient nervous system. But most people should likely start at 2-3 work sets.

- Waves

The only other loading parameter that gave me (and my clients) similar strength gains as clusters are waves. Specifically, 3/2/1 waves.

A “wave” is a series of 3 sets.

With each set you add weight and decrease the reps.

After you completed your 3 sets in a series, you started a new, heavier wave (I normally start the new wave with the weight I used for the second set of the preceding wave). You kept going until you could complete all the sets in a wave. When you couldn’t, or knew that the next set would fail, you stopped.

In any given workout you would complete 2 to 4 waves depending on your recovery and performance state. If you complete 4 waves you either are in splendid form and beat a PR or you started too light.

A typical 3/2/1 wave loading scheme would look like this:

Set 1 – 87.5% x 3

Set 2 – 90% x 2

Set 3 – 92.5% x 1

Set 4 – 90% x 3

Set 5 – 92.5% x 2

Set 6 – 95% x 1

Set 7 – 92.5% x 3

Set 8 – 95% x 2

Set 9 = 97.5% x 1

Set 10 – 95% x 3

Set 11 – 97.5% x 2

Set 12 – 100% x 1

If in a workout you complete 3 waves, at the next session you start with your second wave weights. If you completed 4 waves at the next session you start with your third wave weights. If you only complete 2 waves you stay at the same starting weights. And if you only completed one wave, it’s best to go down 2.5% at your next session.

Of course, because of the high volume of sets and neurological stress, you reduce the amount of work for the rest of the session. A typical 3/2/1 session could use two antagonist exercises with the 3/2/1 scheme and then two antagonist assistance/minor exercises trained in the 6-8 rep range.

Normally a 3/2/1 wave cycle lasts 3-4 weeks in which you can hope to increase your strength by 5-10% on a big lift.

- Doublé

Doublé, for you non-French speaking people means “do it twice”. This is another great strength method aimed at maximizing neural adaptations on one specific lift.

Simply put you do the main lift twice in a workout, at the beginning and end of the session.

Heavy at the beginning and for “volume” or speed at the end of the workout.

For example:

A1. Bench press

3 x 5, 2 x 3

3010 tempo

2 min of rest

A2. Face pull

5 x 8-10

2012 tempo

2 min of rest

B1. Incline DB press

4 x 6-8

4010 tempo

90 sec of rest

B2. Neutral grip seated row

4 x 8-10

2012 tempo

90 sec of rest

C1. Cuban press

3 x 10-12

2020 tempo

45 sec of rest

C3. Straight-arms pulldown

3 x 10-12

2020 tempo

45 sec of rest

D. Bench press

5 x 3 @ 65% for max speed

By doing a lift twice in a session you greatly improve neurological efficiency/motor learning.

“But can’t you just do more sets at the beginning?”.

Of course, that’s an option. Many great programs use that approach. In my layer system, you only do one main exercise using 4 different methods, really piling on the sets.

Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1 with the “Boring but big” or “Boring but strong” assistance work is also such an example.

Or Doug Hepburn plan where you do 8 x 3 then 5 x 5 on the same lift in a same session.

But this works mostly through the shear accumulation of volume and fatigue. Doublés are better for motor learning. One thing I noticed from teaching the Olympic lifts is that there comes a point where when you do so many sets of a same exercise, technique starts to breakdown.

But if you split the sets into two sections you will greatly improve technical efficiency. Remember: the key to motor learning is NOT the quantity of practice but rather the frequency of practice.

By doing a movement twice in a session, it’s like you have to restart the motor pattern acquisition process and it speeds up learning and makes it permanent.

You know what they say about learning: you must learn something, forget some parts, and then learn it again to make it permanent. It’s the same thing with motor learning.

- Time under tension

I was first introduced to the concept of “tempo” by Charles Poliquin probably around 1999 when I first read “The Poliquin Principles”. Tempo refers to the speed at which you perform each rep of an exercise. It is generally prescribed in the form of a 4-digit number. Something like:

4012

The first digit (4) is the duration in seconds of the eccentric phase

The second digit (0) is the transition time before the lowering and lifting phase (time spent in the stretched position)

The third digit (1) is the duration in seconds of the concentric/lifting phase

The fourth digit (2) is the transition time between the lifting phase and the next rep (time spent in the contracted position)

I will admit that I don’t always use precise tempo prescriptions, I feel like it can make training less “aggressive” for many people, decreasing performance. However, what it did teach me was the importance of varying the type of repetitions you do. And that lowering or lifting a weight slowly or fast will have a different training effect.

Doing 8 reps with a 5020 tempo will have a completely different training effect than doing the same 8 reps with a 2010 tempo. In one case, you will create more muscle fatigue, activate mTOR more and accumulate more lactic acid, while in the other one you will use bigger weights and cause more muscle damage.

Playing with the type of muscle contraction is important not only to progress faster, for longer but also to develop your capacity to produce force under different conditions.

- Low reps

I always was a low reps guy. I started training for football and was trained by a good strength coach from the start. The highest we would go as far as reps are concerned was 8 and most of our work was spent doing sets of 3-5.

Then I switched to Olympic lifting, where most of my sets were between 1 and 5 reps.

When I was done with Olympic lifting and wanted to do bodybuilding, I still wanted to do low reps but every bodybuilder in the gym told me that I needed to do sets of 8-12 or more to grow. Charles made it okay for me to do sets in the 4-6 range to grow muscle, and that was liberating.

Heck, I could even do 2-3 reps if I wanted, provided that I slowed down the eccentric or added isometric pauses to increase the time under tension.

While 40-60 seconds is ideal for maximum hypertrophy, you could achieve a combination of significant strength and size gains while being under load for 20-30 seconds or so per set.

By doing a 5-second eccentric phase (thus around 7-second reps) I could still stimulate growth from sets of 3 (21 seconds) to 5 (35 seconds). Heck, I could even do sets of 2 if I wanted, by going VERY slow on the eccentric or by adding a pause in the movement. For example, a 6-second eccentric, 3-second hold and 2-second concentric would last 11 seconds per rep, 22 seconds under load for a set of two reps.

- Have some else do what you hate doing…

I distinctively remember talking to Charles on the phone about having more success business-wise. I was already pretty accomplished as a coach:

- I trained Olympians and even medalists

- I coached pro athletes (hockey and football)

- I worked with athletes from 28 different sports

- I had written 4 books

- I was widely recognized by other coaches as a knowledgeable guy

But this didn’t come with financial success. I was making a decent living mind you, but I kept seeing people who didn’t have half of my knowledge/accomplishments making huge money.

I remember being backstage at a bodybuilding competition for one of the competitors I was working with, and another coach grabbed me by the shirt and presented me to his athlete. The first thing he said was “this is Christian Thibaudeau, one of the smartest men in training. If he were a good businessman he’d be a millionaire”.

Charles being a success both in the trenches and in business, I asked for his advice. And what he told me was to either hire or partner with someone who will do what I don’t want to do or what I’m not good at.

Me, I’m the worst sales person ever. If it were up to me I would do everything for free! I was also not very driven when it came to seeking business opportunities. The few seminars I was giving were simply because people approached me. And I was almost charging nothing for them.

Anyway, I partnered with two guys who palliate for my own weaknesses.

Frederic who is amazingly driven, a great salesman and marketing strategist (neurotype 1A).

Charles-Vincent who is very structured, a great planner and a logical thinker (neurotype 3).

They allowed me to boost my number of seminars to roughly 20-30 per year, for about 10 times the money. They also developed a great business model with Thibarmy.com.

But more importantly this partnership has allowed me to focus on what I love to do and what I’m good at: creating educational material, teaching and coaching. This makes my life both easier, and more successful.

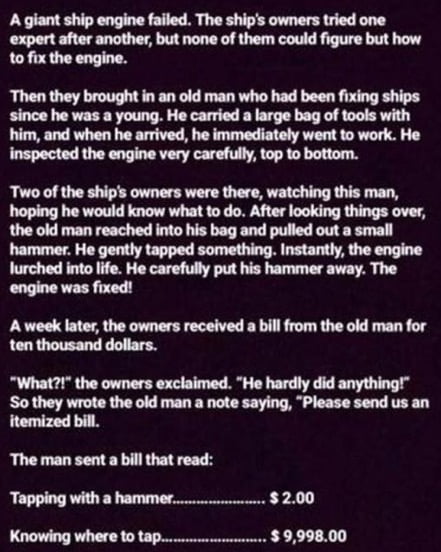

- Know what you are worth

I’ll post a story that explain this next lesson quite well.

For years I was the guy who had problems charging for his services. Here are some examples:

– I started out training elite athletes when I was 20. At 20, I was already training pro hockey players and international level athletes, but I pretty much trained them for free even though they had the money to pay me. I figured that it was good publicity and good experience, and it was, but it also diminished my apparent value.

– When I owned my personal training business and had 6 trainers working for me, all my trainers were charging between 60 and 80$/hour (that was 10 years ago, roughly, and in a small town). But me; the boss, the expert, the main guy, I constantly charged half price for myself!

– When I was in St-Louis, at the Central Institute for Human Performance (working with the great Stephane Cazeault) I was paid a yearly salary, not by the hour. Yet I was the only trainer who would come in on Saturday and Sunday to train clients. For 4 months I didn’t train more than once a week because I didn’t have time.

I would literally train clients for 60-70 hours per week, but I wasn’t getting paid more for all the hours I would put in, so it essentially gave me the equivalent of something like 12$ per hour. And I was training pro athletes, business people, TV celebrities and even a preacher who were all multi-millionaires.

And I could go on and on.

The reason behind this is that I had (still do) very low self-esteem. In my own mind, I was not worth the big bucks. I actually felt bad charging 30$ for a training session when all of the trainers working under me charged 80$.

It took me a long time to accept that I’m good.

I have accumulated knowledge for years. Trained thousands of clients. Put the hours in. I’m a good coach. Much better than many who charge insane amounts of money. You don’t only charge for the program you are building or the session you are coaching. You are charging for all the knowledge you have built over the years.

As a coach, your clients do not pay you for a program. They pay you for your expertise. For finding the solution to their problems. The right approach for them. If you can do that, then you should not be ashamed to charge for your services. Heck, a hairdresser is often paid more than 80$ for a haircut and people gladly pay for it.

I have a coach working under me. He was having problems selling his services. He would sell programs but never any private coaching (which is where the money is in personal training). And the guy is awesome.

He has trained tons of physique/bodybuilding competitors and more than 90% of them reach the podium. One of his female clients went from being a 250lbs alcoholic to a 125lbs physique champion. He is smart and imaginative.

But just like me he had low self-esteem (many of us in this field do). So, when someone walked in his office he couldn’t let his passion shine through because of the lack of confidence in his own competence.

I gave him a one-hour talk, explaining to him why he had problems selling his services (the guy originally designed programs for 20$!) and made him realize what he was worth. The very next day clients were booking 20+ private sessions with him.

And it’s not just about making money. It’s about helping your clients. As a personal trainer you will do a much better job at helping your clients get results if you can work with them one on one a few times a week.

When you are good, when you got educated, gained experience and achieved great results, you need to know what you are worth. When you sell yourself short you might think it makes you look like a good guy, but it really makes you look like the service you provide isn’t worth shit.

- Give credit

Charles was an innovator, maybe the biggest one in the history of strength training, but he also relied a lot on the innovations of others to influence his own methodology.

Most good coaches do that.

But few give credit like Charles did. When one of his methods was influenced by another pioneer like Doug Hepburn or Anthony Ditillo, he always mentioned them. He never felt the need to steal other people’s work to make himself look smarter than he was.

That is a trait that I wish more coaches had.

Giving credit doesn’t make you look any less smart. Quite the contrary. And with the internet and social media, people will easily find out if you stole something anyway.

Always give credit.

- Glycine post-workout

I feel that this is, in retrospect, one of Charles’ best recommendations ever. One that he made 15 years ago as part of a low-carbs post-workout shake. I think even he didn’t realize how effective it could be because I don’t remember him pushing this approach much.

Glycine is one of my favorite supplements, and it’s dirt cheap.

What does it do?

It’s mainly a neural inhibitor. It slows down your neurons.

“Why would I want that?”

Because if your neurons fire really fast you are in what we call “sympathetic mode”, or the fight or flight system. While being there is great for lifting weights, fighting a saber tooth tiger or playing a football game, by potentiating both your physical and mental capacities, it comes with a price.

When you are in sympathetic mode you are pumping a big amount of cortisol. While some cortisol is needed for proper function of the body, too much of it will slow down muscle growth by increasing protein breakdown, myostatin activation and by decreasing protein synthesis.

Over time it can even make it harder to lose fat by decreasing the conversion of the mostly inactive T4 thyroid hormone into the active T3, decreasing metabolic rate.

Being in sympathetic mode too long and too often can also lead to what we call “CNS fatigue”. While the phenomenon is real, the terminology isn’t really accurate. What we call CNS fatigue really is a problem with one of the main excitatory neurotransmitters (dopamine, adrenaline, glutamate), preventing them to do their job (activating your CNS).

We are talking mostly about the depletion of one of these neurotransmitters or a desensitization of their respective receptor.

If we produce too much adrenaline (which happens when we stay in sympathetic mode for too long) we risk depleting dopamine because adrenaline is made from dopamine.

Some symptoms of dopamine depletion include:

- Lethargy

- Lack of energy

- Low motivation and drive

- Drop in libido

- Low pleasure response

- Easily gets discouraged

- Feelings of depression

What can also happen is that if adrenaline stays connected to the adrenal receptors for too long and too strongly, the body can adjust by decreasing the sensitivity of the adrenal receptors, making you a lot less responsive to adrenaline, giving you the following symptoms:

- Hard to get motivated

- Lower muscle tone and strength

- Low self-confidence

- Low energy

- Hard to get a physical reaction

- Less desire to make social contacts

- Slower thinking

- Feelings of depression

As you can see, in both cases we have symptoms of what we call “CNS fatigue”, which is simply a neurotransmitter issue.

Anyway, glycine can help prevent that by effectively taking you out of that excessive sympathetic state when you don’t need to be there. It helps you switch to a parasympathetic, rest and recover, state.

After a workout, your neurons are firing on all cylinders. And if they stay that way for hours after the workout it can contribute to causing the mentioned “CNS fatigue”. By taking glycine post-workout you can more readily enter the rest and recover mode.

You will also decrease cortisol production by the same token.

Another benefit of glycine is that it is a strong activator of mTOR which is, of course, one of the main triggers for muscle growth. So, by taking glycine post-workout you activate mTOR to a greater degree, enhancing the response to your training session.

I personally recommend taking glycine by itself, 3-5g, right after the workout and then having the post-workout shake 15-20 minutes after.

- Peri-workout carbs

While he is traditionally associated with lower carbs eating, Charles was also one of the first proponents of ingesting liquid carbs with protein after the workout. While we now know that in many cases having the carbs pre and even intra workout works even better (I consider myself, along with Milos Sarcev and John Meadows, who pioneered pre/intra workout carbs) ingesting carbs + protein around the workout was a huge step in the right direction and really enhanced gains and recovery.

It sounds trivial today because it’s a strategy that has been used by the majority of serious lifters for 15 years or so, but Charles was the one who popularized this strategy more than 20 years ago.

I personally prefer to have the carbs pre-workout (although in a mass gaining phase you can also have carbs post-workout) for most people. Why?

– It will reduce cortisol production during the workout. Cortisol is in large part released during a session to mobilize stored glycogen to have fuel to do the work. By having the carbs pre and intra workout you have fuel readily available for muscle contraction, so you don’t have the same need to release cortisol.

– It will help drive amino acids into the working muscles. That makes the workout the only time in your life when you can decide where you are sending your amino acids.

– It will preserve muscle glycogen.

You don’t need much, 25-50g pre-workout along with 20-30g of protein will do the trick. Of course, you need carbs and protein that are easily absorbed. Ideally highly branched cyclic dextrins as a carb source and casein hydrolysate, whey hydrolysate or (worst case) whey isolate for protein.

-CT